STORY about Indigenouspublié le Juillet 1, 2017 by Kerry Coast

Smallpox: The Key to Confederation

New book exposes the role of colonial BC officials in 1862 epidemic that devastated west coast nations.

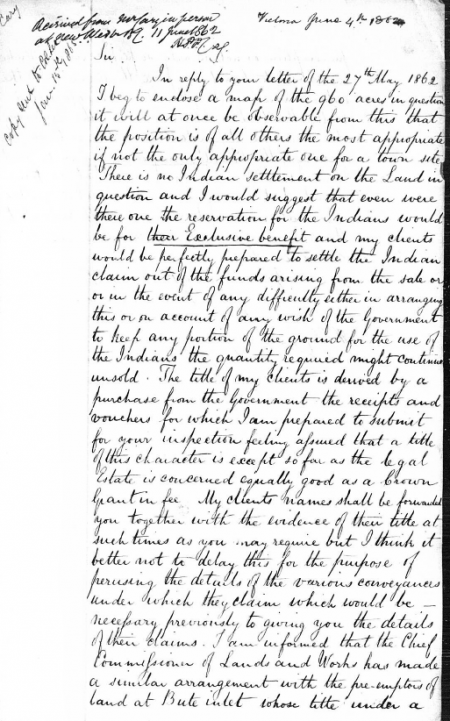

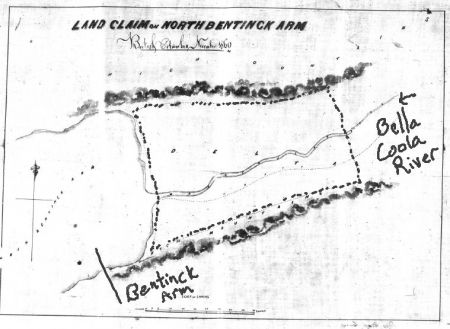

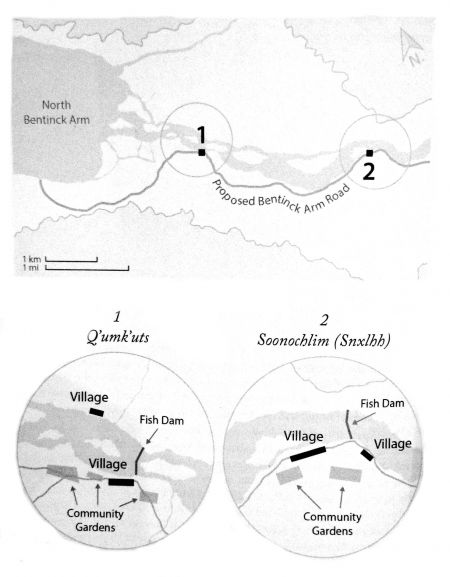

BC Attorney General George Cary's letter to claim lands for his company on the Bella Coola River, describing heavily populated Nuxalk village lands as "empty."

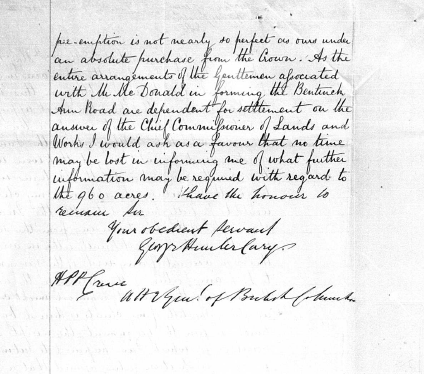

Nuxalk traditional villages, coinciding with the Cavendish Venables 1861 map of the mouth of the Bella Coola River. Diagram from Swanky's book, page 184.

Also posted by Kerry Coast:

Also in Indigenous:

The founding colonial fathers of British Columbia gained control of the land by using smallpox in a pre-emptive biological strike against the powerful Nuxalk, Tsilhqot’in, Haida and other west coast nations, in 1862. This is the latest interpretation of forensically researched letters, journals, maps, records of company directors, and newspapers from the time.

In fact there is a great deal of interpretation in Tom Swanky’s third book, The Smallpox War in Nuxalk Territory. The writer, who holds degrees in law and political science from several Canadian universities, was critically dismissed in his first two publications concerning smallpox and The True Story of Canada’s War of Extermination on the Pacific, largely because of jumped-to conclusions. A turn of phrase in a newspaper article in Victoria really cannot be relied upon to pin an elaborate conspiracy spanning colonial rank, entrepreneurial dynasties and 800 miles of coast.

But he can be forgiven for a little enthusiastic excess, because he has already been convinced of the conspiracy and the evidence speaks for itself – even when the writer is shouting over top of it – confirming the oral histories of every nation which was decimated by disease instead of treatied-with by Britain. And Swanky was dismissed by career academics who have made a living teaching a certain brand of colonial history: one which does not feature genocide and fifteen ensuing decades of active, relentless oppression of Indigenous nations; and which does not feature a past or a future where Indigenous nations are self-determining landlords in their own homelands, free of Canada’s occupation. The smallpox epidemic was the key to British control of powerful, resourceful nations - and their rich lands.

There is a lot of evidence in this new book, evidence which makes that offical, status quo "story of BC" disintegrate. When the pieces of documentary evidence are read together, a sequence of events which deny coincidence can be easily exposed.

Here is the best and most central example: the Attorney General of the Colony of BC, George Cary, formed a company. The Bentinck Arm Company was a speculation venture, planning to get land just before a road from Bentinck Arm went through to the Cariboo goldfields; through Nuxalk and Tsilqot’in country. Cary’s plan was to sell “empty” lots along the mouth of the Bella Coola River, in Nuxalk country, promoting them as desirable properties once the most important new road in the colony, and probably the next major new deep sea port, was built. His Company's shareholders staked claims covering the entire area in 1860. In April of 1862, his Company offered them as being available in June of 1862.

When you put that little artifact next to a map of the mouth of the Bella Coola River, what really jumps out at you is the fact that there were no “empty” spaces along the mouth of the Bella Coola River at the time of his writing. That area was quite full: villages on either side; villages just behind them on the left and right; and a little note as to the population of the 970 acre mapped area – some thousands of people. The Nuxalk did not consider themselves colonial subjects, nor their lands colonial assets, and they were not participants in Cary’s exploit.

In order to sell someone fee simple property, you have to provide “vacant possession” – meaning there’s no one else there. The historical evidence shows that George Cary used a Colony boat to get down to San Francisco in January of 1862, along with a Committee to raise funds for a regular steamship line between San Francisco and Bella Coola, via Victoria. The Committee included several politicans who were also shareholders in the Bentinck Arm Company, and they picked up a couple of guys who had smallpox, and sailed back to Victoria with them. Another traveler, returning to San Francisco when the same ship left Victoria again, gave a report to a newspaper on his arrival: lots up on the Bella Coola River would soon be selling like hotcakes! That was in March of 1862.

In the same month, BC’s colonial officials advised the public there was no money to complete treaties with the nations in whose lands they were squatting. This was a matter of real concern for would-be settlers, because they knew very well that they were not safe without some legitimate land rights. Instead of resources for treaties, the Imperial government of Britain had sent 500 rifles for colonial militias. And Cary had brought two guys with smallpox.

Smallpox spread through Victoria. White people were quarantined, treated, and given vaccinations, while natives, camped in their trading spots on the beaches outside Victoria, were sent home when signs of the disease appeared among them. In fact, their camps were burned down and they were chased away – by gunship, in one case – and the spread of smallpox among their villages followed without delay.

The historical record doesn’t have photos of the smallpox carrier from San Francisco, touching and breathing on native people on the beaches of Victoria. What it does have is Francis Poole’s commission to work for the Bentinck Arm Company – and lead one of the smallpox carriers through Nuxalk, Tsilhqot'in, and then other well-inhabited nations where Cary's company wanted to do business.

The record also exposes the steamship Committee that brought two smallpox carriers back from San Francisco while they were on Colony business arranging for a steamship line to Bella Coola, a line that was being instigated, developed and overseen by the Attorney General (owner of the Bentinck Arm Company) and several former HBC traders who were now in the colonial government as well as being shareholders on the Board of the Bentinck Arm Company.

In May, Francis Poole was sent on to spend some time in the Nuxalk country, along with one of the San Franciscans with smallpox. He led that party in and out of Tsilhqot’in country for the Company. Somehow the smallpox carrier failed to cover his face when in close contact with the Nuxalk and Tsilhqot’in people – somehow failed to keep his distance. Poole, leader of the party and aware of the smallpox they brought with them, somehow failed to provide vaccination, or advise on the vital aspects of quarantine. Smallpox can be transmitted as easily as by skin contact, or on the breath.

By the time June of 1862 came along, Cary’s lots along the mouth of the Bella Coola River were vacant. It takes about two weeks for someone to contract and then die of smallpox, and there were only a few survivors of the epidemic that cleared the Bentinck Arm Company’s lots. Those people moved to live together with the survivors of other villages – they had to, there were so few of them.

There is a lot more to the story of all these people, companies and nations. Those stories are told in great detail in The Smallpox War in Nuxalk Territory. A narrative, a couple of biographies, a timeline and a set of maps make this history accessible and compelling to all kinds of readers.

Swanky set out to prove Indigenous historians correct, he says he did, and so the book reads a little like a murder trial. Well, that’s precisely what it is. It helps to remember that newcomers sitting happily on beautiful, rich lands in British Columbia see that bloody historical mass-murder very differently from the people who are sitting in cramped, poor Indian Reserves in marshes or flood plains or cliff-sides, looking over on what their great grandparents had. And when these two different groups look to the future, they also disagree about what they see there. A “guilty” verdict coming in some 155 years after the fact might actually bring those two visions of reality a little closer together, and prepare people for an upcoming correction on the status quo.

The book:

The Smallpox War in Nuxalk Territory

By Tom Swanky

Dragon Heart Press, 2016

Tom Swanky’s latest book was requested by the Nuxalk people themselves. Although the final text was not approved by them, nor was approval solicited, the book was received very well at the end of 2016 and was followed up by a series of ten workshops by the author in the Bella Coola valley.

In 2014, Tom Swanky was engaged by the BC government to advise on the Premier’s “exoneration” of the Tsilhqot’in Chiefs who were hanged in 1864 for murder and treason. Later this year, The True Story of Canada’s War of Extermination on the Pacific, which covers much of the events surrounding the Tsilhqot’in War of 1864, will be re-released in a second edition.

- Vous devez vous identifier ou créer un compte pour écrire des commentaires

The site for the Vancouver local of The Media Co-op has been archived and will no longer be updated. Please visit the main Media Co-op website to learn more about the organization.