DYING TO PLEASE YOU: INDIGENOUS SUICIDE IN CONTEMPORARY CANADA,

by Roland D. Chrisjohn, Ph. D. and Shaunessy M. McKay

Theytus Books, coming in 2015

Book Review by Kerry Coast

Resistance is the cure for Indigenous suicides. There is nothing “wrong” with Indigenous individuals that was not caused by the relentless violence of ongoing colonization, and therefore the treatment of the fatal condition of dispossession and oppression is to right that basic wrong. That, and an anti-capitalist campaign that will set the humanistic balance of pre-capitalist, or pre-Columbian, economics back in place.

So writes the very qualified lead author Dr. Roland Chrisjohn, Onyota’a:ka of the Haudenausaunee, who published one of the earliest and most accurate exposés of the prevalence of violence against children in Indian Residential Schools, The Circle Game.

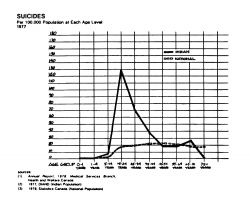

That is, there is nothing inherently “wrong” that makes it reasonable to accept that Indigenous individuals commit suicide ten times more often than Canadians, in some age ranges and demographics. This book undoes the western construct of the “Broken Indian,” a term the authors have coined to refer to the mythical inferior savage, the fictional character which the colonizer has invented as explanation for lack of success and excess of self-destruction among Indigenous individuals.

Dr. Chrisjohn teams with Shaunessy McKay, Mi’kmaq, to reinterpret theories on suicide. Apparently the traditional academic study of this phenomenon has not informed programs which have reduced suicide. And when it comes to a “back eddy” of this field, the main focus of their thinking, the authors have analyzed and criticized the professionals’ approach to Indigenous suicide. “…we're concerned with Native people facing the challenge of unnecessary deaths, of themselves or of others around them. Our goal is to prevent such deaths…”

The authors review the research of non-native psychologists and even self-reflecting ex-RCMP, who pronounce explanations based on the malaise of poverty, poor health, academic failure, drug and alcohol abuse – all considered to be problems which can lead to suicidal behaviour. And all of those writers fail to ask: why is there such a preponderance of these problems in Indigenous communities?

Chrisjohn and McKay adjust the picture to the proper context, by comparing the captive on-reserve Indigenous population of Canada to the situation of concentration camp inmates in Nazi Germany.

Consistent with this parallel, and with the authors’ main recommendation, the Jewish inmates who resisted their captors, fought back and attempted to gain control of their camps, had a survival rate ten times that of those who did not resist. Rates of suicide in the camps were otherwise 50 times that of the general German population.

Looking at the Indigenous situation in Canada, the researchers see individuals faced with a choice like jumping from the top of a burning building or being burnt alive. They say the jump is “not a choice but an inevitability.”

Canada’s working policy ultimatum towards Indigenous Peoples amounts to this inevitability: extinguish inherent rights yourself or see how long you can endure the bonfire of oppression. There is no peaceful mechanism in Canada whereby Indigenous Peoples can engage with the state to resolve the land issues and past harms, even economic sustainability, which does not require the Indigenous party to waive their rights, extinguish themselves as a people, and indemnify Canada. That leaves resistance – or jumping.

What we discover from the authors’ analyses of current approaches is that the mainstream suicidology treatment of suicide among the oppressed is so desperately hopeless that, according to dominant theories of the causes of suicide, the whole study might soon do itself in.

Hopelessness is considered a great cause of suicide. While this rings true for many people who end their lives rather than carry on inside a stack of barriers, when considering Indigenous suicides that hopelessness cannot be separated from the fact that another group of people deliberately stacked up and reinforced those barriers specifically to induce that kind of hopelessness!

Mainstream thinking and theory, courtesy of French sociologist Emile Durkheim’s undisputed (until now) diagrams, cannot even locate the influence of extreme over-regulation in the suicidal impulse. Living within the strictures of the Indian Act might be a good example of over-regulation, but Durkheim found in that corner only the types of oppressive daily regimes such as are borne by young husbands trying to support their families, and does not identify oppression within his map of danger zones in social geography. Durkheim, living at the height of French colonization in Northern Africa, may have had a blind spot where oppressive regimes over-regulating native populations are concerned. The area has not, however, been illuminated in the last century-and-a-half of suicidologists continuing his theories.

“Capitalism is alienation, alienation is oppression, oppression causes suicide.” According to Dying to Please You, capitalism became a force once Columbus reached land in the Americas - and provided an exact location where the Pope could approve of pillaging. Once there were multiple levels in the possession of land and extraction of its resources, the wealthy capitalized on the opportunity and an entirely new class of opportunists emerged – on the backs of alienated workers and African slaves in fields the Indigenous were forcibly dispossessed of.

Capitalism alienates the worker, who does a job to produce a result, from the product of his work. The authors conceive a direct link between this economic model and the material alienation felt by the person who is used as a kind of cog in an industrial machine, never owning any part of what they do but renting out their labour to make it go. For this they rely on a little-known early work of Karl Marx: transcription of a journal and study of suicides in Paris, France early in the 19th century. Marx described alienation as “the human condition under capitalism.” It is not a controversial statement to say that Indigenous Peoples have been alienated from their lands and economies; from their work and all they produce. And whatever roles Indigenous individuals play in the Canadian economy would not bridge that fact.

That oppression flows from material and historical alienation is taken as a pre-formed fact. What this means is that if you have no power to control your identity and your role in history; if you cannot own anything, really; if you cannot even keep that which your expert hands or mind creates; then you are being used. You have no choice but to work, to produce – but someone else is keeping you down and they will benefit from your work, or even from your people’s inherent wealth in this case, while you struggle.

Oppression causes suicide, and Indigenous Peoples are oppressed by Canada.

One of the appendices spells that out in details concerning the “Historic Non-Apology” by Prime Minister Stephen Harper to former students of Indian Residential Schools. The essay was released immediately after the 2008 apology and written by a group of seven academics, including Chrisjohn, and accurately anticipated what APTN has just reported: that the Prime Minister’s own speech writer did, at the time, see it as an “attempt to kill the story.”

Dying to Please You is an important tool for people who have lost loved ones to the “burning building” of Indigenous life in Canada. It is a tool which helps understand, and unpack grief, and forgive, and even rally to the resistance. More importantly, this book will stop someone from committing suicide. It will do this either directly, for a reader, or by informing and empowering a friend who stands between someone’s life and death. And instead of dying, that oppressed person will refuse: she will resist.

“We ask that you refuse to die.” So the authors plead in the last line of the book, having too many times suffered the catastrophe that quakes whole communities when a loved one jumps – and understanding the alternative: informed resistance to oppression, and freedom and independence once again.

Quotes from the book:

“Of all the blather we've had to read about what is going on in the mind of someone at the moment he or she takes the final step to suicide, the only one that has made sense to us is the person who compared suicide to someone trapped at the top of a burning building, having to make the choice between being burnt alive or jumping to his or her death on the ground below. "Why must there be something going on in one's mind when one is driven to the conclusion to jump?," she asked. We agree; whatever is in one's mind at that point, if anything, it is not the determinant of a person's behavior. It is the fire, it is the lack of rescue, it is the unavailability of any alternative that drives the behavior. This is what we wish to say about indigenous suicide: given the situation, it isn't a choice, it isn't a thought; it is an inevitability. It is the inevitability that relentless oppression produces. It is designed to break us, either by driving us over a literal or metaphorical cliff, or by achieving our surrender. But look back at Table 2. Breaking or surrendering are not our only options. We say: there is informed resistance. One can look past the facade of bogus science and erased history and see the real process in action; and in seeing that, understand how it has come to dominate our situation.

For anyone looking for our therapeutic recommendation: here it is. Become informed.”

*

The authors appreciate the freedom of “…a rational, fully-informed person's decision to end his or her life...

“But this is our point. Indigenous people in Canada are not fully informed. We are, rather, systematically mis-informed about the nature of the forces arrayed against us as individual human beings. …we say that the human thing to do is to intervene, to get between a person and death, only because it is so highly unlikely that she or he has made her or his decision having all the information. Does the mass of Indians who commit suicide understand that this is a murder? Do they understand that the murder is being carried out by people under a facade of helping them? Do they understand that, by assisting them in this murder, they are giving their oppressors exactly what they were attempting to get through the means of their murder?”

*

“Canada isn't just trying to kill Native peoples: they are satisfied with some of us killing ourselves, other of us helping keep the great mass of Natives "in line," and the rest of us taking (by various means) our places on the margins of Canadian society. Creating the Broken Indian -- destroyed by ignorance, sex, drink, drugs, and despair, and thus validating Canada's self-aggrandizing, racist narrative of a brown hoard of sub-humans the eurocanadians must rescue, tolerate, and reform -- is more than enough.

“But there is a reason to step back from death, because, as we've argued, to step back from death gives us the chance to step away from ignorance. To do that is to give ourselves time to work through all the reasons we believe we want to kill ourselves; and then, yes, with full information, to complete that act as is our human right. As human beings, we each shall go when we decide it is time for us to go. But if we have the time to learn that we've been misled about what is happening to us and why, the opportunity is presented of doing something meaningful before we take that step prematurely.”

*

How easy it has become for the social scientists of today to do what even the Nazis couldn't bring themselves to do. In truth, does not the history of Jewish suicide during the holocaust, like the histories of suicide in the Arawaks, the Home Children, and the Marshallese Islanders, and countless other oppressed groups, teach us that suicide is in part a normal human reaction to conditions of prolonged, ruthless domination? The dominant depiction of suicide in Aboriginal Peoples inhabiting Canada rhetorically neglects these parallels, biasing those trying to come to grips with the phenomenon away from the readily apparent and into esoteric realms. "Models" of Indian suicide are individualistic, relying on supposed internal characteristics instead of looking at the inverted pyramid of social, economic, and political forces impinging on Aboriginal Peoples. Existing explanations blame the victim, finding that they suffer from personal adjustment problems or emotional deficiencies like "low self-esteem" and "depression." None of the existing explanations alleviate the situation by acting or suggesting action against the forces of oppression; they don't even recognize them. The cost-effectiveness of the government's providing perfunctory, end-of-pipe social intervention programs instead of meeting their contractual treaty obligations doesn't surface as an issue.

- Vous devez vous identifier ou créer un compte pour écrire des commentaires

The site for the Vancouver local of The Media Co-op has been archived and will no longer be updated. Please visit the main Media Co-op website to learn more about the organization.