STORY about Housingpublié le Mai 26, 2014 by Tyson Leonard

“It’s a question of what unites us”

An interview with Harold Lavender on accountable structures, systemic change, and the peril and promise of alliances against gentrification.

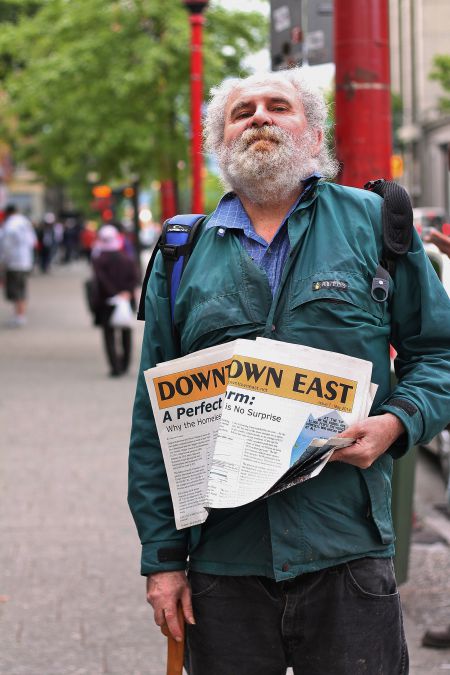

Harold Lavender has been involved in many struggles for social justice, and in recent years has been focused on the anti-gentrification movement in the DTES. Photo by Tyson Leonard

Also posted by Tyson Leonard:

Also in Housing:

This is the third in a series of conversations with Vancouver-based anti-gentrification activists. These conversations will culminate in an article with an in-depth look into the effects of gentrification on Vancouver communities and the strategies being proposed to resist and ultimately stop gentrification.

In the first interview, I spoke with Karen Ward about the unique community of the Downtown Eastside (DTES). In the second interview, I spoke with Richard Marquez on the pressing need for diversity within Vancouver’s anti-gentrification movement.

In this interview, Harold Lavender speaks on organizing the anti-gentrification movement and on which structures best resist gentrification.

Harold Lavender has been involved in many struggles for social justice, and in recent years has been focused on the anti-gentrification movement in the DTES. He is a member of the Social Housing Alliance and the Downtown East, as well as being involved with other groups in the DTES community.

What are some of the specific strategies for organizing people to fight gentrification in Vancouver?

One of the main focal points is community organizing, and that’s what I’ve been involved in. One of the slogans here in the DTES is “Nothing for us without us.” That is a really important slogan, because what happens is that decisions about what happens to the use of urban space are being made by people who aren’t accountable to us. That includes large real-estate corporations who make the economic decisions, and city politicians who put on a show of consultation, but in reality are developer funded. So basically it’s a question of how communities get back that control, and the power to make decisions that affect their lives.

A lot of the community organizing in the DTES is based on people’s experiential knowledge in the community, such as the experience of oppression. This is a community where people interact with each other, and have spaces and organizations, and shared experiences and values. So that actually provides a certain capacity to resist oppression. That’s what we’re trying to do, draw on the collective strength of the community.

You also have to try to create organizations that are inclusive of the community. One of the myths about the DTES is that it’s a stereotypical community, or it’s not a diverse community. In fact it’s a really diverse community, and it includes a lot of different experiences. So it’s a question of what unites us, while remaining aware of class, gender, racial, and colonial oppression.

I think people want to live with dignity—they want to have a real community, a community that stands up for justice and is caring, and doesn’t share the predominant values of a capitalist society based on consumption and individualism. The people living here don’t want condos, they don’t want fancy restaurants, they don’t want places that exclude them, and they don’t want to be harassed by the police. Many people want to remain in the DTES but with better housing and conditions of life.

What are some of the structures that are able to resist the government policies that contribute to gentrification?

The community organizations that don’t accept those policies, and provide a forum for organizing that allows for the participation of people in the community. They have to be really accountable structures. And there can be different kinds of structures. But we need to mobilize and be visible in the streets. Groups can do this in different ways, with some being more willing and able to use more confrontational and direct action tactics, such as organizing tent cities and occupations, et cetera. The main thing is still that there has to be some sort of accountability though.

One of the things people are doing is organizing the tenants in the hotels, and getting them to take the lead. Structures that don’t work tend to involve people who are not directly affected, who then try to speak for the people that are most oppressed, but never have to live with the consequences. Those are the kinds of structures that aren’t ok.

There also needs to be various kinds of alliances, because there is obviously a lot of different issues that tie in to gentrification. For certain things, peer-run structures are really central, but the main thing is to support people’s agency. So the leadership has to come from the people in the communities who are suffering the consequences, but of course you need allies to succeed. So on the one hand we need to strengthen the resistance within the DTES, but on the other we really need to find alliances on a city-wide level.

How do you make people who aren’t directly affected by gentrification care about what’s happening to areas like the DTES, and parts of traditionally working-class neighbourhoods in East Vancouver?

Most intense forms of gentrification are concentrated here in the DTES, but lots of other people are facing issues of rent increase, lack of tenants’ rights, and being displaced by economic issues. The majority of people in Vancouver are renters, and a lot of those renters live in a precarious situation where they pay way too much of their income towards housing. Some people have talked about appealing to the middle class; that’s not really the way I see the issue. We might have some common issues with other communities’ organizations, but the problem with that is to find a way you can ally yourself without your issues being subordinated.

Often you find that people really don’t know what’s going on, and they’re horrified when they find out, and then they’re willing to do something. So there are people you can appeal to who support social justice. I think the more people know and can humanize the situation the better they can help. People have a bunch of stereotypes that just get in the way and you need to break them down and make them see they are dealing with real human beings. Neo-liberal gentrification favours private interests over the common good. This is not the world many people who make a living wage aspire to.

What are some of the ways that developers and their allies are pushing through gentrification policies?

They have a very powerful lobby group, and they also have a tremendous influence over the capitalist process here in Vancouver. They also tend to operate behind the scenes with private meetings. One tactic they’ve used is they’ve begun to increase their influence in non-accountable public bodies. For example, Bob Rennie, the condo king, was appointed to the board of directors of B.C. Housing. So obviously B.C. Housing’s policies are changing in a very negative way. And they completely control the Development Permit Board; it’s a totally helpless body. So basically, developers and the people with power get together, and the people without money are excluded.

The City (Vision Vancouver and city staff) sometimes tries a co-operative and consultative process like around the DTES Local Area Plan, but in the end imposes its own pro-gentrification agenda, with only minor mitigation, and ignores the needs of the low income community.

Do you think it’s possible to successfully stop gentrification within the neoliberal capitalist structure we live in?

Personally, I feel that we need to try and change the structure, but I think there is a problem if it’s an either/or. People are being hurt by government policies, and they need to be able to deal with the problems at hand. But I think the more people struggle in ways that build independent organizations, the better. And sometimes those struggles can be a catalyst for systemic change. Personally, I think systemic change is necessary—without it it’s hard to get to the root causes of the problem, and gains won through past struggles are at constant risk of being taken away in a time of austerity. But I don’t like the either/or.

Tyson Leonard is a journalism student interested in adversarial journalism, and is currently interning with the Vancouver Media Co-op.

- Vous devez vous identifier ou créer un compte pour écrire des commentaires

The site for the Vancouver local of The Media Co-op has been archived and will no longer be updated. Please visit the main Media Co-op website to learn more about the organization.