STORY about GenderSolidaritypublié le Avril 26, 2010 by fazeelajiwa

Death Does Not Become Her: The Fourth Night

When Battered Women Are Arrested

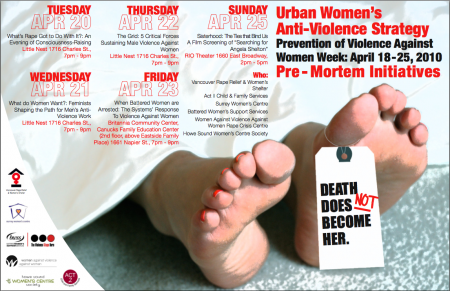

On Friday night, the Urban Women’s Anti-Violence Strategy hosted the fourth discussion in a week-long series of events held during Prevention of Violence Against Women Week. This is a new coalition comprised of independent women’s groups from the lower mainland who have joined together to criticize the Solicitor General’s Domestic Violence Action Plan for focusing the province’s resources on risk assessment and a death review panel, both of which take place after violence has already occurred. The Urban Women’s Anti-Violence Strategy calls for recognition of the essential role that independent and equality seeking women’s organizations play in ending the systemic inequalities that perpetuate violence against women.

The night’s topic was painful but timely: a rising trend of women being themselves arrested when calling on the state for protection from a violent man. Lisa Yellow-Quill, representing Women Against Violence Against Women, pointed out the subtext of woman-blaming inherent in the criminal justice system and in our social fabric. Rape myths that warn women against walking around late at night or wearing certain clothes put the responsibility of assault on the woman. “Women do not make the choice to be assaulted by a man, men make the choice to assault – but when a rape is reported to the legal system, there is an expectation on women to defend themselves as the most moral and ethical course of action.”

This responsibility to defend assumes that she could have stopped it in the first place, and if she did not try, then she implied consent. Yellow-Quill referenced the famous Ewanchuk case in which a seventeen year-old girl was sexually assaulted during a job interview that took place in Ewanchuk’s trailer, despite asking him to stop several times. Ewanchuck was first acquitted on the basis that the girl implied consent by staying in the trailer. At the Supreme Court level, Ewanchuk was found guilty and Madame Justice L'Heureux-Dube is on record recognizing mythologies about women that the trial judge had used in acquitting Ewanchuk. Today, consent laws have been changed so that consent must be explicitly obtained and given – it cannot be “implied.”

Despite these victories in the criminal justice system, rape crisis centres still find that few cases of physical or sexual assault make it past the initial investigation, and that there is a rising number of women being arrested when they try to call for help. “If we are raped, we must defend ourselves, if we do not defend ourselves then we are responsible for the rape, and if we do defend ourselves then we can get arrested,” Yellow-Quill said.

Rosa Arteaga revealed to the room that Battered Women’s Support Services had gathered 25 cases in which women were arrested for incidents of violence committed against them. 70% of the cases involved RCMP, and in 70% of the cases, the accused were immigrant women (most of whom spoke little to no English), or women of colour, or aboriginal women. Arteaga had permission to share the appalling story of one woman involved in this study. The woman had stayed with her abusive male partner because of his promise to sponsor her. She had tried to call police in the past, but stopped after threats that he would ensure her deportation and she would never see her child again.

The incident that led to her arrest began when he strangled her. She managed to call 911, at which point the man grabbed the phone and told the operator that she was trying to kill him with a knife. While he locked himself in the bathroom, she grabbed her child and went outside to wait for the police, who interviewed him before forcing her into the car. Due to her lack of English, the only words she understood were “we are going to take your child.” While they were driving, cops stopped to ask a passerby if he understood Spanish, and when he said yes, they asked him to translate while they read her rights.

She spent 4 days in jail with no translation and no knowledge of where her child was, despite the fact that the “victim” had no marks on his body. When she was released, she was taken to a transition house by the police – which is significant because it illustrates that the police acknowledged she would be safer in a battered women’s shelter than at home with him. The workers and Arteaga secured the woman family and criminal lawyers, and fought with the Ministry of Children and Family Development on the basis that they had no proof of her bad character since there had been no investigation.

On the stand, the police officers that had arrested her could provide no notes they had taken at the scene, and when asked for evidence they produced the knife – which had not been fingerprinted. The 911 tape clearly recorded the woman crying “he’s lying!” and the man telling the operator that he had the knife, before changing his story to say that she had it. From past relationships, this man had previous charges of assault from the Burnaby and North Vancouver RCMP detachments. The police officers had failed to conduct a thorough investigation.

Kristy Howey, also representing BWSS, pointed to two major problems: the lack of policy consistency between detachments, and the incident-based nature of the criminal justice system that does not take context into question. In all 25 cases, the women were victims of sustained violence. The RCMP have a primary aggressor policy that requires history and context to be taken into account (though the language points to “the most compelling” rather than the first aggressor, and also implies a secondary aggressor), the Attorney General’s policy makes no mention of the primary aggressor policy and the Crown is not required to take the history of the relationship into context. Lee Lakeman, a collective member from Vancouver Rape Relief and Women’s Shelter, observed that “all levels of policing must still be responsible to the Charter – and that means they have a statutory obligation to develop equality for women.”

Lakeman outlined the history of feminist gains from the state from 1973 until 1995 when structure of funding for social welfare programs changed in favour of repaying national debt. Since then, the Canadian women’s liberation movement has struggled for state provisions as basic as funding for rape crisis centres. In response to an audience member advocating for voting in more women, Lakeman pointed to community organizing as key to achieving the social transformation that is necessary for equality gains for women. “We cannot abandon community strategies. When we got concessions in the past it was because we were doing more direct action. We need to be more troublesome, more ungovernable, cost them money, stop traffic, interfere with banking and advertising. We are entirely too obedient, and voting doesn’t change that – it’s a shuffling game.”

Lakeman also recognized that the forces holding men’s power in place spread farther than the state apparatus, and relying on community organizing can be problematic for women too (for example when influential male community organizers are the violators). “We have to keep choosing between the power of the community and the power of the state, because we don’t really have a choice. We have to keep both strategies.”

Serena Bains from the Surrey Women’s Centre reminded the audience that the Solicitor General’s domestic violence reforms do not acknowledge the history of independent women’s organizations in the anti-violence movement. The government’s Action Plan repackages grassroots anti-violence work that was started by feminists, and serves it back to the community in the form of “victim service” work that removes the context of gender in the violence that happens overwhelmingly to women. As all of the panelists pointed out, a commitment to the eradication of violence against women requires deeper policy changes than what is outlined by the Solicitor General’s reforms.

Fazeela Jiwa is an independent journalist who also works for VRRWS.

The site for the Vancouver local of The Media Co-op has been archived and will no longer be updated. Please visit the main Media Co-op website to learn more about the organization.