STORY publié le Mai 7, 2011 by d.

Reviews: Fort Armadillo and The Last Days of Mankind

Also posted by d.:

Aussi dans:

The recently released and much celebrated documentary film Armadillo is titled after a command base of the Danish armed forces in the Helmand province of Afghanistan. The documentary follows a group of new recruits from Denmark to the base where they and the film crew spend six months.

Shot in the neo-new-wave-euro-realist fashion of uncomfortable close ups and shaking hand cameras, this framing of war mimics the European film style in its existential story as well.

Choosing five morons, it allows each to express their emotions as a unique singularity, each over bloomed in their private and vast universes, each a warrior king over the world. Every sideway glance and blink edited in slow motion eludes their innermost psychologies. These individual subjectivities are grouped into a form-of-life which has become the more dominate in our culture at the end of civilization. That this film is the first to document their rise to war, gives it great importance, and raises questions as to its framing.

Following Judith Butler’s argument, such frames of war not only necessitate an investigation into what they are projecting, but perhaps more importantly- how these images are allowed to be reproduced. In recent years war propaganda has taken on the aesthetic of hipster culture. A drab disassociation, a valorization of the individual, hyper ironic, a proclivity for nothingness. These features create a fertile enough swamp of complacency towards imperial plunder, but what if empire actually wants to recruit these emo-jocks into armed service!?

The agents of war have solicited the expertise and adventurism of artists to conceptualize this new frame of war. Of course movies and videogames have forced war efforts to adapt to their style of massacres and mayhem, but now documentary films and post-modern art stylize the battle for the sensitive-nihilist. Truly an Army of One, the singular soldier is encouraged to explore the subjectivities of guilt and horror, but as experienced threw a rite of passage which insists upon a detached violence. In the film two goons sit close, the one is in tears rocking him self. He has just learnt that a young girl has died from injuries suffered from a mortar he fired. His companion in a soothing voice comforts him with compassion and says:

"No use worrying over spilled milk. We live in a world, where you watch the news with thousands of people, who die all the time- so it doesn’t bother me if a girls dies. Its just because your close to it. I just think… we came down here, and it wasn’t done on purpose. We did exactly what we were supposed to do, and we would do it again. That’s the way it is."

Where the film best gives a frame to this postmodern subjectivity of war is the condescending hostility of the Afghani farmers who are forced to deal with these idiots who stomp threw their fields in their ridiculous looking clown suits from outer space. On routine patrols the soldiers are swarmed by kids, and try shooing them away to no avail. ‘I don’t owe you any money’ the one yells in Danish. Two young boys approach the one solider and ask,

What are you Jewish or Christian?

Christian!

English or Canadian?

Denmark!

Why are you here, don’t you have a home? You are going to die here!

Their fathers meet the clowns with the same disdain and humor. A pompous field commander and translator greet a group of farmers who are obviously reluctant to be seen with them-; after awkward and imposing small talk:

-We desire you cooperation-

Farmers all laugh heartily

-Cooperation in driving out the Taliban… so we can build a school for your children.

-You have guns and they have guns. You ruin our field and kill our animals. When you leave they would cut our throats.

Continue laughing and shoo them away.

Even back at base the specter of command casts no authority. A farmer with a grin of contempt stares down the room of soldiers:

Soldier through Translator: we are sorry we destroyed your fields, but you know why.

Farmer: how should we know? It’s our fault maybe? Last year you bombed our house. I swear by God I don’t even have any clothes to wear, and my sons can’t help me.

Translator: it’s not our fault we try to minimize-

Farmer: then we must leave our villages. What can we do? What can we do? It’s not you or the Taliban that gets killed. We are the ones who get killed. The civilians get killed. We sit in our homes and get bombed. The Taliban shoot us and get away. They escape.

Translator: we are sorry, but we try to move the war up north-

Farmer: that would be good for us, for this ruins everything.

Solider through Translator: hopefully you can cooperate in getting the Taliban out of the area-

Farmer: you cant! People fight because they are poor. Including the Taliban.

In two other cases farmers come to the camp to petition financial reimbursement for things they never owned, pointing to evidence known to be false, such as a fake grave and trees long ago destroyed. The commander doles out the money, like a welfare worker giving a crisis grant. This is the only cooperation between the occupiers and the occupied; the rest is bloodshed.

Meanwhile the goon-warriors rot in inertia. There is no way the film can depict the time that passes, where boredom, which has oft been diagnosed as the root of all evil, putrefies their psyches. Degrading porn and violent video games, calling home to mom and dad. Sitting on a cot. Sitting at post. Anxiety to kill. To go home with that story to tell. The boredom is ruptured only by massacres. Then a return to boredom.

The Last Days of Mankind

It is the temporality, more then empathy for the precarious lives, which the frames of war fail in translating. The empathy is already rooted in the viewer, either for the suffering of others, or for the boredom. But it is for space and time that Karl Klaus deemed Mars as the only suitable theatre for the production of his play, The Last Days of Mankind. Coming in at over 800 pages, 500 characters, prologue, five acts, epilogue, and spanning across half of Europe during world war one.

Collected during the war, the play is a collage of documents and interviews that he transcribed into the mouths of characters based and named after them selves. As he stated in his introduction; "the most improbable deeds reported here really happened. The most improbable conversations that are carried on here were spoken word for word. The most glaring inventions are quotations. Sentences whose insanity is indelibly imprinted on the ear grow into a refrain that stays with one forever. A document is a dramatis persona; reports come to life as personae; personae breathe their last as editorials; the feuilleton acquires a mouth that speaks itself in a monologue. Intonations race and rattle through time and swell to become the chorale of the unholy action."

Amongst the gore and banality of butchery, Klaus weaves dialogues of satirical tragedies that transmit so naturally into our contemporary joke of media:

The subscriber and the patriot conversing:

Patriot: well, what do you say now?

Subscriber: what should I say? If you’re perhaps referring to Sir Edward Grey’s eye trouble, well then I say, they should all have it so bad!

Patriot: true, but what do you say to the muzzling of public opinion in England?

Subscriber: sure, I know about that, the publisher of the labor leader was called before a magistrate because certain disclosures in his paper violated the Empire Security Act. Just imagine!

Patriot: and in France, what happened there- isn’t it something? What do you say about France? Do you know what’s going on there?

Subscriber: of course. A man said that France didn’t have any ammunition, and for that they gave him twenty days! He said the allies were in a bad way and that Germany was armed for war-

Patriot: please, could you explain that to me- for I don’t understand these cases. Is it untrue then to say Germany was unarmed or is it true to say Germany wasn’t armed-

Subscriber: well, was Germany armed?

Patriot: so how-?

Subscriber: now keep in mind once and for all. It’s a known fact that Germany was suddenly attacked- as early as march 1914 Siberian regiments-

Patriot: of course.

Subscriber: Germany was then completely armed for a defensive war, which it had long wanted to wage, and the allies had long wanted to wage an offensive war, for which, however, they weren’t armed.

Patriot: now you see, the apparent contradiction is clearing up for me. Sometimes a person is ready to think something is true and yet it isn’t.

Subscriber: in the papers its often easy to get a good overview from two columns running right next to each other. This arrangement has the advantage of clearly indicating the difference between us and them.

Patriot: well, did you read this? Plunder and devastation by Italian soldiers! In Gradisca they took no less than five hundred thousand kroner out of one safe and, besides that, twelve thousand from another!

Subscriber: I read that. A band of thieves! What do you have to say of the colossal success of the Germans?

Patriot: didn’t read that, where was that?

Subscriber: what a question! Right on the next column! It doesn’t seem to me that you read it in an orderly fashion-

Patriot: right in the next column? I must have skipped over it. Where was this success?

Subscriber: at Novogeorgievsk. “Gold in the Booty from Novogeorgievsk” was the headline.

Patriot: well, what was the story?

Subscriber: the story was that there were two million rubles in gold in the victory booty at Novogeorgievsk.

Patriot: fabulous! Whatever the Germans touch-!

Scene change.

At the end of the play is a string of apparitions, which arrive and disappear:

Dying men in the barbed wire in front of Przemysl.

(The apparition vanishes.)

Close combat and the mopping up of a trench

(The apparition vanishes.)

A schoolroom into which an aerial bomb falls.

(The apparition vanishes.)

A solider is pulled out of a mass of earth. His face is streaming with blood. He spreads out his arms. He has been blinded.

(The apparition vanishes.)

A double apparition: a German officer who shoots down a French prisoner pleading for his life. A French officer who shoots down a German prisoner pleading for his life.

The sinking of a hospital ship.

(The apparition vanishes.)

Flanders. In a plundered hut, a figure in gas mask sits in front of a kettle. On his lap, a smaller gas mask.

(The apparition vanishes.)

A horse, upon whose back the outline of a gun is etched in blood, appears.

(The apparition vanishes.)

Winter in Asinara. Prisoners strip comrades who have died of cholera. Starving people eat the flesh of those who have starved to death.

(The apparition vanishes.)

The front lines in Carpathians. All quiet. In the trenches corpses stand upright, their rifles ready.

(The apparition vanishes.)

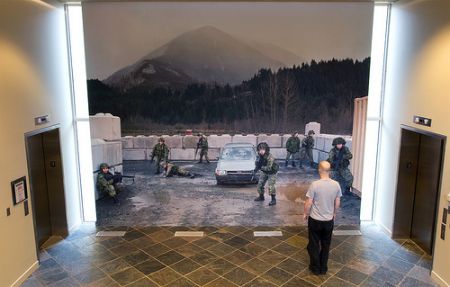

Although there was no montage in the Armadillo film-, but there was an overabundance of other embarrassing formulas-, one could perhaps be made here so as to weave a continuum of wars' eternal recurrence. Here, we use just clips from the film; but one could only begin to imagine the ocean of violence that would be reflected from a similar montage of The War on Terror.

From the small patch of Afghanistan and to the oscillation of Scandinavian heavy metal:

- Farm animals being sliced open by shrapnel and debris

- Three figures running threw a field are suddenly engulfed in an explosion

- An effigy of a Taliban fighter is set ablaze while soldiers drink beer on lawn chairs

- From a surveillance plan, in green night vision, a series of huts are bombed

- Mothers beg a cease fire to remove the dead children

- In a ditch the corpses of three Taliban fighters are shot 30-40 times at close range after being blown apart by a grenade

- Alongside the road, an improvised explosive devise has gone off, causing damage to the armored personal carrier. A farmer bleeds to death in the dirt

What method is used to frame war is a tactical decision made by the partisan war machines against empire. As Judith Butler went on to say regarding the what-and-how’s of the image’s reproduction, ‘the operation of the frame, where state power exercises its forcible dramaturgy, is not normally representable- and when it is, it risks becoming insurrectionary, and hence subject to state punishment and control.’

The recuperation of the captured frames, which help us in our dissemination of enmity against the state, is civil war against war.

Klaus wrote himself into his play as the character ‘grumbler’ who spent his numerous scenes debating the optimist:

Grumbler: That this war, the war of today, culture does not renew itself, but rather saves itself from the hangman by committing suicide. That this war has been more then sin; that it has been a lie. A daily lie, out of which printer’s ink flowed like blood, the one nourishing the other, streaming out in several directions, a delta toward the great sea of insanity. This war should be ended not by peace, but rather by a war of the cosmos against this rabid planet!

Optimist: you are an optimist. You believe and hope that the world is coming to an end.

Grumbler: no, it is only running its course like my nightmare, and when I die, it will all be over. Sleep well!

The site for the Vancouver local of The Media Co-op has been archived and will no longer be updated. Please visit the main Media Co-op website to learn more about the organization.