STORY about Peace/Warpublié le Novembre 2, 2015 by Kerry Coast

"War on drugs" wipes out people, not trafficking.

New documentary book connects foreign investment to terror in Latin America: Drug War Capitalism by Dawn Paley.

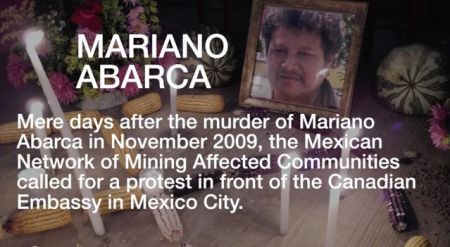

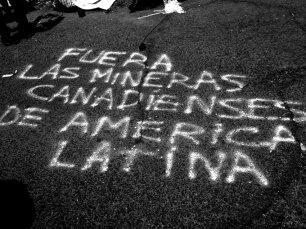

Employees of Calgary mining company Blackfire were implicated in the assassination of a local Chiapas man who spoke out against mining.

Fortuna Silver, based in Vancouver, operates in Oaxaca State, Mexico, where local peoples are violently oppressed to secure foreign direct investment.

The Canadian International Development Agency helped fund and write major revisions to Colombia's oil extraction and transportation policies. Canadian oil companies operate in Colombia where para-military units are known to be engaged in securing foreign-owned extractive industries.

The United States of America's Agency for International Development has been extremely involved in Mexico and Colombia, carrying out police training, re-education of lawyers in US-style judicial processes, and even the re-writing of various legislation. In 2012, USAID funds trained 8,500 prosecutors and investigators; 22,000 police officers and 100,000 students. They are currently opening more police training mega-centers.

This new documentary book connects foreign companies to terror in Latin America: Drug War Capitalism by Dawn Paley.

Also posted by Kerry Coast:

Also in Peace/War:

Drug War Capitalism

By Dawn Paley, Foreword by Guadalupe Correa-Cabrera

November 2014, AK Press

The “war on drugs” as it is known in the USA and Canada is not what people have been told, Dawn Paley argues in her first book, but is effectively masking a war on people.

Incidents of torture, terror, disappearance and eventually displacement of local peoples in Colombia, Mexico, Guatemala and Honduras reach into the hundreds of thousands. This new book documents that violence in connection to securing the interests of foreign direct investment - not to drug-related events.

The revelations of Drug War Capitalism are stunning, horrifying and deadly serious. “It’s a US occupation and narco-trafficking is the justification,” says one of the remarkable sources Paley has interviewed. In the foreword, we are told “The most important contribution of this book is its extraordinary explanation – utilizing different cases in the four countries of study – of how the state violence displaces urban and rural populations, leading to changes in land ownership and resource exploitation.”

At least equally important is the extensive documentation of US and Canadian interference in those countries’ domestic affairs. This story has been researched and confirmed from foreign policy development stages in Washington, DC, through villages and towns depopulated after local militarization; increased drug production even while the “war” is advancing; changes to environmental legislation to permit more oil production and transit; the extractive industries’ establishment in the newly vacant lands; paramilitary security around foreign mining and oil and gas operations; and back to Senate reports in the USA, which reconfigure the chain of events in a cloud of mystery and recommend supplies of more guns to stop the murder and disappearance.

Cooperation of state and corporate (US backed) military achieves militarization of the countries and security for foreign direct investment.

Fernando Roa, farmer and Vice President of Santo Domingo’s communal action council, Colombia, explains: “This is a policy of the government: to clear us off the territory that is ours, as campesinos and Indigenous peoples, because there are many Indigenous communities who have their lands taken away by war, by the terror that they instill in the communities to remove us from our territory so they can come and extract natural resources.”

Drug War Capitalism is not a collection of nouns but identifies a new type of capitalism. This is the multi-faceted approach to modern multi-national mercantilism in lands where the people don’t want the extractive industries. This is capitalism advancing by chasing a phantom of its own making.

Prohibited drug production and distribution is used as a justification for militarization, while the actual target is displacement of collective land owners from lands coveted by multi-national extractives.

The criminalization of cocaine, marijuana and heroin creates a climate of prohibition in which "anything goes" and interested entrepreneurs do business amid escalating violence and retaliation. “Security” initiatives by the state do not seem illogical.

However, when military forces arrive in an area, supposedly to wage war on prohibited narcotics, suddenly that area becomes the murder capital of the country. These operations tend to happen in areas of interest to foreign development. The military presence forces drug production to move, and supply lines re-organize elsewhere, but the military stays until the area is quite depopulated. The bodies are counted to indicate progress is being made in the war on drugs – even after the drug traders have moved on – and the bodies are often dressed up in outlaw uniform and guns put in their hands. As one of the book’s interviews goes, “the people who are killed… don’t have guns.”

This journalistic inquiry shows Canadian and American companies conducting business in Mexico and Colombia under the protection of that system. Foreign investment doesn’t seem to leave militarized, violent areas – it actually thrives and increases there! Former cartel operatives, as well as execution squads used by Guatemala in the 1980s – the Kaibiles, form the units armed by the USA to “fight the war on drugs.” These units often secure oil pipelines, access to mines, and defeat uncooperative collective land owners – in areas with no narcotic history.

USAID and CIDA involvement in re-writing Mexican and Colombian legislation, police organization and education has protected extractive industries and encourages foreign direct investment, supporting politicians friendly to FDI at any social cost.

A “paramilitary” force is usually understood as military units which operate at arm’s length, or completely separately from, state forces. But that is no longer always the case, as these highly organized groups, “unionized criminals,” according to one of Paley’s sources, seem peculiarly consistent in acting according to a bigger picture of state militarization and legislative re-organization around foreign direct investment.

Because there are other significant parallel processes. Known as the parapolíticas, elected officials in Colombia, Honduras and Mexico shadow box with the “unionized” criminals mentioned above, and bend legislation and political will the way foreign direct investment requires.

Paley has included in her investigation some interesting facts about the re-education of lawyers and police in Mexico, as well as the re-writing of oil extraction legislation in Colombia – all funded by Canadian and US international development aid. The juxtaposition forces the reader to consider the presence of a parajudicial process as well.

The drug war capitalism model is proving satisfactory to those who promote it: USAID money goes back to buy American guns; pay American military contractors; protects American investments; and leaves the other country with the social and environmental bill.

Paley is a freelance journalist who has reported from South and Central America and Mexico for the last ten years. Fluent in Spanish and willing to go to areas other journalists don’t, the author has made the connection between terror and free trade in her accessible investigative journalism style.

Among many heretofore unimagined interview subjects are Don Henry Ford, a Texan who explained how he introduced better marijuana seeds to farmers in Mexico in the 1970s, telling them “this is what we want.” The head of Columbia’s industrial workers union confirmed his observations of direct links between industry and paramilitary. A Mexican political candidate spoke loudly with Paley at a café, just months before the elections he was running in, about the state’s use of military and police units trained and armed by the USA’s Merida Initiative, or “Plan Mexico” – to wage the drug war – instead to protect foreign interests. (He didn’t get elected; he was arrested and detained during the lead-up and the vote.)

When she asked the best known peace activist in Mexico, Javier Sicilia, who could confirm the link between state actors, drug traffickers and terror, he told Paley, “ask anyone.”

Paley interviewed qualified people about the 2009 Honduras coup. The incumbent Zelaya was inclined towards increased representation and constitutional review, and he had already raised teachers’ wages and cut school tuition. He was removed from his home the day before a vote on creating a constitutional assembly and kept in Costa Rica for four months until Hondurans went to the regularly scheduled polls and elected a new president, one who was available, and whose first slogan in office was “Honduras is open for business.” Canada and the USA immediately joined Honduras’ business elite by recognizing the new government as a legitimate progression of popular change. 54 activists in support of Zelaya were murdered between June, when he was removed from the country, and November, when Lobo Sosa was elected the new president.

This type of murder is so common as to produce such grassroots organizations as the “Committee for Relatives of the Disappeared in Honduras," "Justice for Our Daughters" in Mexico, and many others throughout the four countries of study.

From the "war on drugs" emerge regimes of terror south of the US border, as evidenced in journalistic silence, and, at the other end of the spectrum, organizing by peoples' groups on the exact subject of disappearance and victims of violence.

All the while, our globalized “para-media” keeps its focus on good guys chasing bad guys.

In the tradition of Open Veins of Latin America and Confessions of An Economic Hitman, Paley has helped redefine who are the bad guys, and placed in sequence the truth of capitalism without competition in Mexico and the countries just south of it.

In 1982, Indigenous communities living in Guatemala’s Rio Negro valley, the site of intended reservoirs for the World Bank’s Chixoy Dam, were labelled communist terrorists. Peoples who rejected and opposed the dam, and all the flooding that entailed, were all gunned down by a wave of soldiers pushing through the jungle – and the world was told those peoples, whole communities, were guerrilla soldiers bent on terror.

Soldiers responsible for the Guatemalan genocide, in such crews as the Zaibiles, now head many of the paramilitary units justified by America’s “war on drugs” in Columbia and Mexico.

Today, the innocent farming and Indigenous peoples who object to mines, dams and pipelines are labelled drug traffickers. They are then attacked en masse by paramilitary forces, ignored by parajudicial processes, maligned by parapolitical opportunists, and misrepresented by the paramedia.

Those people, those bodies posthumously dressed up in camouflage outfits and belatedly armed with weapons, have names. And in most cases someone has found them, identified them, and testified to the event that brought about their untimely deaths: the war on people.

Drug War Capitalism will soon be released in Spanish, with a new Afterword by the author.

Read an interview with Dawn Paley.

Check out Dawn's site.

Quotes from the book:

“The most important contribution of this book is its extraordinary explanation – utilizing different cases in the four countries of study – of how the state violence displaces urban and rural populations, leading to changes in land ownership and resource exploitation.”

- From the Foreword by Guadalupe Correa-Cabrera.

“This is a policy of the government: to clear us off the territory that is ours, as campesinos and Indigenous peoples, because there are many Indigenous communities who have their lands taken away by war, by the terror that they instill in the communities to remove us from our territory so they can come and extract natural resources.”

- Fernando Roa, farmer, Vice President of Santo Domingo’s communal action council, Columbia.

“This project… looks at how, in this war, terror is used against the populations in cities and rural areas, and how, parallel to this terror and resulting panic, policies that facilitate foreign direct investment and economic growth are implemented. This is drug war capitalism.”

As Uruguayan social theorist Raúl Zibechi notes, “It will be difficult for capitalism to survive if it fails to consolidate new forms of control and subjugation.” According to geographer David Harvey, the expansion of capitalism depends on accumulation through dispossession, which can include forcible displacement, the privatization of public or communally held lands, the suppression of Indigenous forms of production and consumption, and the use of credit and debt in order to facilitate accumulation by dispossession, among others. All of these things are occurring in Mexico today…. And the war on drugs is contributing to the acceleration of many of these processes.”

- From Chapter One.

- Vous devez vous identifier ou créer un compte pour écrire des commentaires

The site for the Vancouver local of The Media Co-op has been archived and will no longer be updated. Please visit the main Media Co-op website to learn more about the organization.