STORY about MediaArts posted on November 6, 2010 by Andre Guimond

Crit crit: Return to El Salvador (Documentary)

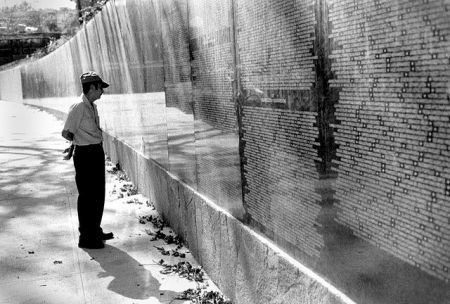

The 'Monumento a la memoria y la verdad' in San Salvador, commemorating the over 70,000 killed in the civil war

Also posted by Andre Guimond:

Also in Arts:

Crit crit is one part cultural review and two parts media criticism, poured over crushed ice and mixed into a 140-proof ether of analysing and challenging the culture industry – not just for the kick of, like, getting totally wasted on criticism, but as an infinitesimally small part of the ongoing project of defining the contours of a liberated and participatory culture and society.

Director Jamie Moffet’s brief documentary exploration of the last 30-40 years of the tragic and violent history of El Salvador should be applauded for its accuracy and for accomplishing, in part, its clearly stated goal: spreading awareness of the tragic history of Central America’s smallest country, long a victim of American intervention and the cruel whims of its own ruling class.

With Martin Sheen narrating, Return to El Salvador starts by rushing through the grim facts of the 1980-92 civil war between the leftist Farabundo Martí Front for National Liberation (FMLN) guerrillas and the right-wing military dictatorship: over 75,000 dead, mostly innocent civilians; the assassination of archbishop Oscar Romero in 1980 and soldiers opening fire on crowds at his funeral, setting off the war; mass repression by the ruling oligarchy and military junta - all with US support.

After the prompt backgrounder sets things up, the personal stories of two Salvadoran couples, Sonia and Luis Ramos and Ruth and Alex Orantes, and their courageous activism in the US after being forced to flee their home country take center stage. (“The only way to survive was to go to the mountains and join the guerrillas, or wait in your house for the death squads,” one of the involuntary exiles recalls.) Although oddly stiff in parts, these detailed and emotional accounts of the horrors of life during the civil war go a long way towards helping us understand the incredible suffering faced by Salvadorans.

For instance, upon Alex’s return to his home in El Salvador he recounts seeing a group of young teens, doing nothing more than hanging out and chatting at a street corner, suddenly thrown into a truck by Salvadoran soldiers – an oft-employed fear tactic during the war. He cries as he remembers the teens’ dead bodies being dumped out of the truck after it passed just another two blocks, the young boys’ penises shoved into their mouths. Stories like this are where the film is most effective, quite simply because the intended audience (North Americans, primarily) has never experienced anything in their home country that begins to approach the level or types of terror and violence that were pervasive in El Salvador.

The film also succeeds in highlighting the fact that few improvements were made after 1992 when the civil war and open armed conflict officially ended. In fact, another 23,000 civilians have been killed this decade alone, largely by paramilitaries made up of the same military death squads that were responsible for rampant atrocities like the one described above. Unsurprisingly, the very same elite sectors of society that supported and implemented the mass murder regime 20 years ago still enjoy the same power and privilege today. The war may have ended, but little has changed: wealth and the interests of the powerful rule all.

Where Return to El Salvador stumbles, though, is in a rushed presentation that is sure to turn some viewers off (and give an excuse to critics to dismiss the film completely, as we’ll see below), and more importantly, in its scattered and somewhat tentative examination of the US government’s key role in installing and supporting the Salvadoran terror regime – a role intimately connected to the “underlying conditions [which] still exist,” as Sheen often mentions but doesn’t expand upon. Although a lot of the facts are covered, as will be seen shortly, they aren’t tied together to bring forward the full scope of (or reasons for) US interference – an important connective piece that the film would have benefited greatly from.

The Big, Nasty Picture

To be fair, the documentary does include a short but accurate overview of the causes of the conflict, which helps brings the full story together. In about a minute Sheen covers everything from the invasion of the Spanish conquistadors to the rise of the modern Salvadoran oligarchy in the 20th century, to elite opposition towards Vatican II-inspired liberation theology (which centered on the radical pacifist message of the gospels; a clear threat to the ruling class as it organized the poor against gross inequality) and the assassination of Oscar Romero, its most visible advocate, which sparked the FMLN insurrection and the ensuing civil war.

On the topic of American intervention, the film notes that at the peak of its atrocities the Salvadoran military dictatorship was being funded by the US government at a rate of $1 million a day. There is also a portion of the film dedicated to the School of the Americas (SOA), the infamous US military academy which trained Latin America’s death squads in horrendous methods of torture and murder. “It’s a school for terrorists,” says a Salvadoran woman witness to the SOA-trained death squads in action during the civil war. According to a former US official, though, the SOA was “designed to train Latin American military to be more effective and updated, and also to be democratic. The problem is that the School of the Americas has become a symbol of the US military’s interference in the internal affairs of Latin American countries.” This implies that having created Salvadoran assassin teams that purposefully targeted innocent civilians was an unforeseen consequence of training soldiers working for a fascist military dictatorship in the cruellest methods of torture, terror and death (oops!) – and that the SOA is simply a “symbol” of American intervention, rather than an instrument of it, as evidenced by the 75,000 Salvadorans killed by these US-trained maniacs. This official happens to support closing the SOA, but only as a symbolic gesture and primarily as a way for the US to “gain in reputation.”

The twisted mindset that underlies comments like these is something the film could have examined carefully, but instead we are given footage of a candlelight vigil held in support of closing the terrorist training facility. Of course it’s important to highlight grassroots American opposition to state crimes, but if the film is directed (as it claims) at raising awareness, the lack of a larger narrative is highly problematic. It’s kind of like giving someone the keys to all the apartments in a building and asking them to unlock each door, then not telling them which building it is.

For better insight into the causes of the civil war in El Salvador, and to understand the extent of and reasoning behind US intervention, an excellent article by Noam Chomsky can be found here.

In general, it is first important to know that high-level US planners have long regarded Latin America as the “backyard” of their empire. The notion that America has some claim over everything south of its borders (at the least) stems from the expansionism that has characterized US policy from the very start – and which Latin America has felt the consequences of since at least the 1846 Mexican-American war wherein the US annexed half of Mexico, now better known as Texas, Utah, Colorado, Arizona, New Mexico and California. Reacting in part to revolutions in Mexico, Guatemala and, crucially, Cuba, in the early-to-mid 20th century, and in response to increasingly independent economic and social development throughout Latin American – an obvious threat to US investments, business interests and control over the region – the US began overthrowing democratically elected governments, beginning in Brazil in 1964, and installing business-friendly military dictatorships in their place.

This sent a clear and lasting message about the American love of democracy to those who cared to notice: democracy is great for countries to have, but only insofar as it accommodates US business and political interests. Otherwise, military dictatorships are much more preferable.

In El Salvador, the above mentioned rise of peasant, labour and other organizing associated with liberation theology and the powerful idea that people have the right to make decisions about their own lives without outside interference, combined with US ally Somoza’s degrading control of nearby Nicaragua (a strategic US base for control over Latin America), convinced planners to increase their material and diplomatic support of the ruling military junta in order to suppress the rise of democratic tendencies in the country – and the broader region, by example. The leftist FMLN waged a guerrilla war in an attempt to overthrow the dictatorship, and Reagan cried “Communism!” as a way of justifying the intervention, which secretly included sending in US soldiers to fight the rebels in 1981-82 – a fact that went unknown and unacknowledged for nearly 15 years. Tens of thousands of peasants, students, activists, priests, teachers, labour organizers and other clear threats to society were murdered to teach the Russians a lesson about having nothing to do with the situation, and conveniently, to consolidate power in the hands of the Salvadoran elites that stood to benefit most from helping out their benevolent American friends.

In the Chomsky article above, we find a hint of the nature of the death squads’ methods, which are telling of the utter contempt of those calling the shots towards anyone willing to challenge their right to power:

“The results of Salvadoran military training are graphically described in the Jesuit journal America by Daniel Santiago, a Catholic priest working in El Salvador. He tells of a peasant woman who returned home one day to find her three children, her mother and her sister sitting around a table, each with its own decapitated head placed carefully on the table in front of the body, the hands arranged on top ‘as if each body was stroking its own head.’

The assassins, from the Salvadoran National Guard, had found it hard to keep the head of an 18-month-old baby in place, so they nailed the hands onto it. A large plastic bowl filled with blood was tastefully displayed in the centre of the table. According to Rev. Santiago, macabre scenes of this kind aren't uncommon.”

Again, it is important to be clear that Return to El Salvador does a great job of telling the basic story, although in a fairly disjointed fashion. A lot of the essential facts are presented, but the corresponding insights and overarching narrative are sorely lacking.

While it’s obvious that Moffet and Sheen’s hearts were in the right place, missing out on the big picture – and, importantly, not keying in on the full extent of American involvement for an American audience – not only ensures that the documentary is limited to raising awareness of El Salvador’s current situation but also does little to elucidate central and ongoing world-defining issues (the nature of US intervention, increasing militarism, which sectors of society most influence policy and action, what “democracy” actually means in foreign policy terms, etc.).

Barry and Jason’s Lurching Gut Reactions

So, what did the Canadian media big leagues have to say?

Starting at the conservative end of the media spectrum, it’s no surprise that the National Post’s Barry Hertz sees the presence of celebrity activist and “ultra-left” (a very high level of left-ness, right between gnarly-left and cowabunga-left) narrator Martin Sheen as a warning sign that watching this film means you’re in for some “light propaganda.” Although Barry finds it “difficult to argue with the film’s call for social justice,” he still wished the film was more “balanced” and “cinematic.” Translation: the film should have also told the heartfelt story of the murderous oligarchs and their US advisors, and throw in more wide-angle shots and some soft blur effects. Strangely, though, even with a clear anti-“left” bias on display, Hertz proceeds to accurately and uncritically restate the facts that Return to El Salvador presents, but finishes by calling it a “flaky, one-sided production.”

In contrast, Jennie Punter at The Globe and Mail is dead on in calling the documentary “kind of a mess.” She also notes the lack of an overarching narrative as a weak point, criticizes Sheen’s brevity when it comes to covering important facts, and thinks it could have been more impactful had Moffet let the stories of the couples returning to El Salvador carry the film – all reasonable comments. While her review focuses on how the film plays out and speaks very little to its contents, at least Punter had the tact not to attack it for failing to hold to abstract values like “balance” and “cinematic”-ness like our buddy Barry above.

The writers at the Post and the Toronto Star must go to the same screenings; again, the propaganda accusation is thrown around, this time with Jason Anderson at the Star calling the film “agitprop” by the implication that those are the kinds of films that Sheen does voice-overs for. In both cases, it’s interesting to note that what was shown in the above analysis to be an accurate and honest account of El Salvador’s recent history (although sorely lacking in structural analysis) is claimed to be propaganda, an attempt to control people’s minds, by members of the mainstream media, without evidence or even further comment. It’s hard to tell whether this is an indication of some deep-seated bias at work, the pressure of a deadline and need for sensationalism creeping in, or just plain old lazy writing. Otherwise, though, the Star’s review pretty much just sticks to the facts – which, again, is strange, isn’t it? It seems obvious that if one has found something to be “agitprop” or “propaganda,” they might then spend some time explaining the contradiction between the message and reality – you know, what it is that we’re supposedly having our minds controlled about– but that doesn’t happen in either case here.

At the other Toronto paper, the Sun, Liz Braun (of QMI Agency) gives the film a positive review, calling it “fascinating” and basically just summarizes the documentary. Par’s the course at the Georgia Straight, and the reviewer clearly picked up on Return’s purpose as a “tool designed to tell North Americans about what they can do to help.” Over at the “ultra-left” end of the media spectrum, June Chua of rabble.ca delivers a thorough summary of the documentary and even points out things she learned from the film and wasn’t aware of before. Chua is clearly sympathetic to the plight of the Salvadorans (really, how can you not be?) and intrigued by the first-hand stories; like others she thinks that there were “elements of an even better documentary buried in Return to El Salvador” but since it has “many focuses” and fails to make the returning Salvadorans’ stories more central, it loses its impact.

All in all, apart from the reactionary and unsubstantiated propaganda claims of the Post and Star, the media’s coverage and criticism of the film is pretty accurate. In a way, it seems that by sticking to the facts and not delivering a stronger narrative about US interference in Latin America, the overriding power of wealthy interests, or what have you, Return to El Salvador is somewhat insulated from further criticism. (Just imagine what Barry would have said if words like “capitalism” or “imperialism” were ever uttered in the film…) The flip side of that, though, is that it would be perfectly reasonable to walk out of the theatre wondering how all these seemingly disparate facts fit together, or that perhaps it’s all just unfortunate happenstance, an “accident of history,” as Florida’s new Republican Senator Marco Rubio likes to think of the Cuban revolution.

The truth is, as we began to explore above, there is a bigger story to tell, one that connects all the facts together and ultimately, I believe, needs to be told if Moffet’s goal really is to rally people to solidarity with the Salvadorans and make lasting changes that will put an end to US meddling and the interconnected exploitative economic and political systems we’re saddled with today. As Chomsky notes, “The problems of Latin America and the Caribbean have global roots, and have to be addressed by regional and global solidarity along with internal struggle.”[1] Return to El Salvador very much falls into the category of global solidarity, and despite struggling to connect the puzzle pieces of the facts it presents and straying too often from its strongest parts – the stories of the returning Salvadoran couples – this film should be recognized for its accuracy, its message of hope with the election of FMLN candidate Mauricio Funes, and its valuable contribution to raising awareness of the struggle of the Salvadoran people.

[1] Noam Chomsky, Hopes and Prospects (Chicago: Haymarket Books, 2010), 118.

The site for the Vancouver local of The Media Co-op has been archived and will no longer be updated. Please visit the main Media Co-op website to learn more about the organization.