STORY about Peace/War posted on December 11, 2017 by Kerry Coast

Delgamuukw versus The Queen

20 years later, Gisdayway family produces searing report on a legacy of dispossession and division following the court ruling that Gitksan and Wetsuwet’en title survives.

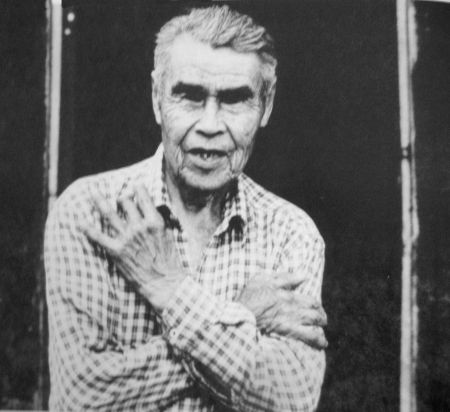

Art Loring, Eagle Clan, blockading the CNR in Gitksan territory, from the film "Blockade," by Nettie Wild.

Niist Gravehouse at Slamgeesh, Judge Alan McEachern looking on. Photo by Peter Grant in book Colonialism on Trial

In the book "Colonialism on Trial," artist Don Monet depicted the government's lawyers as crows. Gitksan people - in their resilience in court - had likened the crown lawyers to the trickster figure of Wyget.

Also posted by Kerry Coast:

Also in Peace/War:

On December 11, 1997, the Supreme Court of Canada ruled that British Columbia has not extinguished Gitksan and Wet'suwet’en title and rights. The watershed case collected essential elements of previously recognized Aboriginal rights and articulated a clear sum of those parts: Aboriginal title and rights have not been extinguished by the province; Aboriginal title is a real, economic interest in the land; and Aboriginal title affords the owner the right to use the land and choose what it can be used for.

After December 12, 1997, thousands of column inches rolled off the presses of BC’s daily newspapers in protest. Everyone who made a living in BC was making it off the back of resources extracted from non-treaty, unceded and unsurrendered Indian land, and they were not about to let a legal ruling interrupt that. Farmers, loggers, exporters, truckers and all the businessmen in between drew up their position much in the same way US President Andrew Jackson did, when Justice Marshall said the Cherokee owned their homelands: The judge has made his ruling, now let’s see him come and enforce it!

Well, it wasn’t enforced any more effectively than in Georgia, where Jackson marched the Cherokee away along the Trail of Tears.

Twenty years of unabated logging and mining and development later, the ruling has informed a handful of cases that advanced the legal character of Aboriginal rights – at least, Canada’s definition of those rights. But what has changed on the ground? What is the real legacy of Delgamuukw, when eighty cents on the BC dollar comes directly from extractive industries, and the Indigenous are as poor as ever?

Chief Na’Moks, a Chief of the Tsayu (Beaver Clan) of the Wet’suwet’en, commented on the anniversary of Delgamuukw Day:

When the SCC overturned BC’s Court Decision, we were elated, but that was short lived as the decision has been continually ignored. We hoped that BC and Canada would uphold the Ruling, but they, and industry, chose to “Bury their Heads in the Sand” and pretend it did not apply to them. Continual approvals of Proposed Projects have proven this to be a fact.

According to Ron George, Wet'suwet’en of the Gisdayway lineage, destitute are the grandchildren of those Chiefs who sacrificed a decade of their own lives to protect their lands and bah’lahts – hereditary governance system – in the Canadian courts. That, and the fact that even the Supreme Court of Canada is no match for the governments’ insistence that Indigenous peoples will be ruled according to the state’s convenience, is the subject of his academic report: YOU’VE GOT TO PADDLE YOUR OWN CANOE.

At the time of the trial in BC Supreme Court, 1987 to 1990, George was president of the United Native Nations, based in Vancouver. Urban Gitksan and Wet'suwet’en raised funds to support the cause, and UNN offices housed UBC law students who were supporting the legal teams when the trial was moved to Vancouver. George, along with most of his family, did not have Indian Status. Gisdayway, the leader of their house, refused to leave home on his ancestral lands and move to the Indian Reserve. So fervent was his refusal that the Indian Agent concerned simply, unilaterally, enfranchised Gisdayway – Thomas George, and his wife Tsaybaysa - Mary George. His home was registered as pre-emption. Enfranchisement was a Canadian torture device designed to further the destruction of Aboriginal nations, creating “Non-Status Indians” who could not live on Indian Reserves nor participate in any of their business, nor exercise Aboriginal rights.

They still can’t, in spite of the fact that the Supreme Court of Canada ordered a new trial into the Gitksan and Wetsuwet’en complaint to better articulate:

that the common law should develop to recognize aboriginal rights (and title, when necessary) as they were recognized by either de facto practice or by the aboriginal system of governance.

- Delgamuukw v. British Columbia, 1997 SCC, at 159

The new trial was never held. A combination of factors must have interfered: the financial cost – the three year trial, then the longest in Canadian history, came in at $23million; the cost in lives – a number of Chiefs and Elders died during the trial of stress-induced strokes and heart attacks, one of the laments in PADDLE YOUR OWN CANOE; and that the people believed their vindication at court would be enough to force the province to deal fairly.

The Delgamuukw case can certainly be understood as the highest colonial court’s check on a province that never bothered to make treaties with Indigenous Nations, but the machinations of colonialism in British Columbia are grizzly. As McEachern J. explained the colonizer’s view at the time, in his 1991 ruling on the trial in BC Supreme Court: no Aboriginal title or right could survive the presence of British subjects and the operation of their laws in this place.

The trial and the 1991 BC Supreme Court ruling

On March 8, 1991, the BC Supreme Court ruled against 71 Houses of the distinct Gitksan and Wetsuwet’en nations, in their attempt to prove sovereignty and jurisdiction in their homelands. The ruling was a devastating event. “It was the one day in my life that I was going to quit the practice of law. I just felt I had misled 69 Chiefs and hundreds of people to believe there was some kind of justice in this country,” Peter Grant, one of the plaintiffs’ lawyers, later said of the ruling.

69 Chiefs had stood together to launch the case against The Queen and see it through the courts over a seven year period. They decided the first Chief named, so the case would carry his name, would be Delgamuukw. His position at home was that of the Chief who brings all the other Chiefs together after a day of discussion and debate.

The first words spoken in the trial were this: “My name is Gisdayway and I am a Wet'suwet’en Chief and a plaintiff in this case. My house owns territory. Each Wet'suwet’en Chief’s house owns several territories. Together we own and govern Wet'suwet’en territory.” Chief Delgamuukw, Gitksan, spoke next:

For us the ownership of territories is a marriage of Chief and land. Each Chief has an ancestor who encountered and acknowledged the life of the land. From such encounters come power. The land, the plants, the animals and the people all have spirit and they all must be shown respect; that is the basis of our law.

The case was launched in 1984, amid blockades against logging and a Gitksan blockade of the CN Rail line, which eventually had forty trains backed up on either side and strangled off the northern BC port. Direct action was a second-last ditch attempt to stop the clearcutting that was bankrupting the land-based peoples, as no legal avenue was open and the governments were not negotiating circumstances around the total devastation of the peoples’ natural wealth.

A documentary film from the time, “Blockade,” by Nettie Wild, captured the moment when RCMP are denied entrance to the Gitwangak Indian Reserve and directed to proceed along their “so-called right of way” – the train tracks. There on the rails the police read out an injunction for the train blockaders’ removal and Art Loring, Eagle Clan of Gitksan, standing in the middle of the track, replied:

Pointing to a very old totem nearby: I’d like to draw your attention to that pole there. Those poles tell us we’re right. We own this land; not the court, not the province, not the federal government. That’s why we do this, because we have a right to. And your courts come in and take us away because you think you have a right. We don’t agree. We’ve lived here far longer than you guys have.

My name is ten thousand years old. My wife’s name is twelve thousand years old.

The last ditch was to sue The Queen for recognition of their sovereignty and jurisdiction. Between 1987 and 1991, the trial encompassed 374 days of argument and evidence: 318 days of testimony. There were 61 witnesses; 53 territorial affidavits; 23,000 pages of transcript evidence at trial. The Elders brought forth their way of life and presented it, through translators, to the court. Gwis Gyen (Stanley Williams), for example, said this:

All the Gitksan people use a common law. This is like an ancient tree that has grown the roots right deep into the ground. This is the way our law is. It’s sunk. This big tree’s roots are sunk deep into the ground, and that’s how our law is.

The results of the litigation were immediate, terrifying and violent. Logging in the territory accelerated. Native school children in Hazelton and Moricetown were beaten and dumped in ditches, informed by their white attackers that “this is for the land claims!” And 400 pages of written reasons, reminiscent of 19th century colonial logic, were afforded by the presiding judge, Allan McEachern.

Chief Justice McEachern, as he was then, was not circumspect about his contempt for the plaintiffs. He failed to see how the presented histories, maps, villages, house posts, clan system or hereditary titles, demonstrated any sort of ownership or identifiable governance. The province of BC argued, “Clan membership is even less helpful as a way of identifying the membership of the society of Gitksan. A Clan is not a corporate body. Clan membership is a way of lining people up at Feasts, of determining who is host and who is guest, and it is a way of organizing a rule of incest.” McEachern dismissed the Elders’ oral histories. In his reasons for dismissing the plaintiffs, he described them as “vagrants” whose lives were “nasty, brutish and short.” Peter Grant put it this way:

It was an opportunity lost. The man who heard the case as the judge did not have the capability of understanding or hearing what was being said to him.

“Treaty process” follows denial of rights

A few months later the report of the BC Claims Task Force was released, and, without a hint of irony, the BC Treaty Commission was in business a year later – with the express purpose of negotiating the extinguishment of Aboriginal rights. A paradox to be sure, since the province’s Supreme Court had just decided there was nothing to negotiate.

This move repeated the governments’ response to the Calder decision of the Supreme Court of Canada in 1973. There, three judges reasoned that the Nisga’a title to Nisga’a lands had never been extinguished. Although the case was dismissed as inconclusive – three other judges disagreed and the seventh refused to rule – it was the first time Aboriginal title had won any judicial support at all. Calder was immediately followed by the introduction of the Comprehensive Claims Policy: a mechanism by which Aboriginal rights, including land rights, would be negotiated away before they were acknowledged as such. The Nisga’a engaged in that, along with four other “test cases” from across Canada.

It was during this time, at least by 1997, that the Supreme Court of Canada decided Aboriginal title was a form of Aboriginal right. This, they said, protected Aboriginal title in the Constitution of 1982, under Section 35, where, “The existing aboriginal and treaty rights of the aboriginal peoples of Canada are hereby recognized and affirmed.” Judicial definition of these rights has progressed along a marked departure from the Indigenous position that Aboriginal rights flow from Aboriginal title, or, what Indigenous people meant when they said “Aboriginal title” does not seem to be the same thing that Canadian judges mean when they use the phrase. Indigenous peoples, for instance, don’t seem to agree that their title can be infringed as required by Canada.

The Supreme Court’s reasoning perpetuated fundamental colonial constructs that are anathema to reconciliation. The judges repeated the problematic notion that aboriginal rights are sui generis – a Canadian invention to mystify Indigenous property rights and attach an “inherent limit” on Aboriginal title. And the judges continued to rely on the idea that Great Britain gained sovereignty over the west in 1846 – as they pronounce to this day – simply because Britain had made treaty with every other European power that had previously expressed interest in the area.

In court, the Gitksan and Wet'suwet’en Chiefs categorically rejected the statement of British sovereignty over their lands. Unfortunately, they had given their question over to the jurisdiction of a BC court in the first place. That is the kind of conundrum Indigenous Peoples are in: if they go to a Canadian court for legal recourse against Canada, they will find a judge who is Canadian. It’s an obvious conflict of interest which has resulted in widespread Indigenous appeals to third parties out of the state, to the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights, and to United Nations treaty bodies and Special Rapporteurs.

DISC – then and now

In 1997, the Supreme Court of Canada overturned several of McEachern’s decisions and routed his reasons so that they could never be used again.

The next day, the front page of The Vancouver Sun newspaper featured a huge picture of Edward John, Chair of the First Nations Summit, stating his expectation that the ruling would revolutionize the state’s negotiating mandate within the BC treaty process. The ruling had said, after all:

Aboriginal title encompasses the right to exclusive use and occupation of the land held pursuant to that title for a variety of purposes, which need not be aspects of those aboriginal practices, customs and traditions which are integral to distinctive aboriginal cultures. The protected uses must not be irreconcilable with the nature of the group’s attachment to that land.

Surely selling 98% of Aboriginal title land to the state, to be developed and parceled off as fee simple title, was a use “irreconcilable with the nature of the groups’ attachment to that land.” But that was about to become the precedent for engagement under the BC Treaty Commission.

Against the First Nations Summit’s suspended disbelief, a group of Indigenous leaders formed to propose a bridge between the ruling and Aboriginal rights on the ground: the Delgamuukw Implementation Steering Committee. “DISC” attempted to gain traction with the Assembly of First Nations and the federal government, to hammer out practical ways and means for Aboriginal peoples to benefit from the ruling. But the initiative was supplanted by an exploratory committee that eventually resulted in the First Nations Governance Institute.

The 1997 decision did not change the federal government’s policies concerning negotiated extinguishment, which is now referred to as “modified rights” and includes a First Nation’s indemnification of the state for “all past harms. Robert Nault, as Minister of Indian Affairs in 1999, stated that Canada wouldn’t do anything to alter its “flagship process,” the “made in BC” answer to treaty settlement (and renegotiation) across Canada. Ten years later, Minister of Indian Affairs Chuck Strahl stated that the BC Treaty Commission was not a rights-based approach. In 2009, three years of work by a Chiefs Task Force working with government negotiators at a Common Table reached a final impasse in attempts to bring treaty negotiating mandates up to a minimum that could be seen as equivalent to Aboriginal rights already won in Canadian courts.

Last month, the federal government announced a new sort of DISC: the Department of Indigenous Services, Canada. The Department of Indian Affairs (also known as INAC, AANDC, etc.) was cleaved in two, separating land claims from the administration of Aboriginal-specific (ie, underfunded) works and programs like health, education and welfare. The new DISC refers to the latter, while the iconic Canadian “Indian land question” will be split off into version 3.0 of the Comprehensive Claims Policy / BC Treaty process / post-Tsilhqot’in decision… which apparently does not have a name yet, according to government press releases, but will be managed by a new Ministry under Carolyn Bennett: Crown-Indigenous Relations and Northern Affairs.

Cases building on Delgamuukw

In Haida, 2004, the Supreme Court ruled that government agents had a duty to consult and accommodate Aboriginal peoples whenever they contemplated action, such as resource licensing, which might impact Aboriginal title – proven in court or not.

The legal brain trust of the colonial state has diverted whatever relief that ruling might have offered into dissipating channels of “consultation” and “accommodation,” through such mechanisms as Forest and Range Agreements and other revenue sharing agreements. Thus, Aboriginal peoples attempting to benefit from that legal decision have the option of signing off that their economic interests have been accommodated – to mobilize Forest Resource Management Plans, sometimes as yet unwritten – for a paltry per-capita sum. Instead of spending a decade in court, or watching business go on as usual. It’s a provincial scheme sculpted around the lowest common denominator that meets the government obligation to accommodate economic interests in Aboriginal title.

In 2007, the William case resulted in a preliminary ruling in the BC Supreme Court for a Declaration of Aboriginal title in Tsilhqot’in. Seven years later, that case resulted in the first ever declaration of Aboriginal title in Canada. The case followed the method of proving Aboriginal title which was defined by the Delgamuukw case.

Jack Woodward has been legal counsel for the Tsilhqot’in since the 1980s. He commented on today’s anniversary and what might happen next:

The next step is obvious to me, but perhaps that is because I am a lawyer who thinks constantly about the remedies that are available within the legal system. With Delgamuukw and Tsilhqot’in, and many other decisions, the courts have opened their doors to Aboriginal people to use the powerful tools found in Section 35 of the Constitution – Aboriginal title, Aboriginal rights and treaty rights. These are some of the most powerful tools known to our legal system. They are there to be used. I believe that the use of those tools is as full an answer as we can ever expect to the questions of decolonization. In the 20 years following Delgamuukw, Aboriginal people have been very restrained about the use of the courts to seek the available remedies.

According to Ron George’s new report, the governments have found even better ways to get cooperation for resource extraction and development: funding elected Band Council Chiefs to attend the Hereditary Chief feasts – where national business is done; and even funding the purchase of traditional positions within the Feast Hall. The government’s licensing bureau ensures that no Hereditary Chief or his family can avail themselves of their own natural wealth on the land base, by recognizing only the authority of offices which conform with Indian Act / Band Council modes of operation. This action is, in itself, the most fundamental exercise of bad faith on the part of Canadian governments – although the examples are many and chilling – in the legacy of Delgamuukw.

Those three syllables will resonate in the annals of Canadian history forever: dell-gah-MOOQU. And what will this name call to mind? That Al McEachern got paid. That Indigenous Peoples will never stop fighting for their right to exist as a people, even when the colonizer’s government ignores its Supreme Court. That Canadian indifference to law is a matter of global significance.

In, YOU’VE GOT TO PADDLE YOUR OWN CANOE, Ron George notes the following legacy:

Although some people call the Indian Act an artificial barrier, Atna feels that barrier is very real and is manifested by these attitudes toward us when we ask questions they are unable to, or choose not to, answer. “At one traditional meeting, a chief told one of our family, ‘Well, you should be so fortunate that we allowed you back on reserve’. That was in a Wet’suwet’en traditional meeting. …the whole purpose of the court case was to address that and try to move it away…get away from that. We hang onto it. [our people] hang onto it because it’s a power base…and there’s authority that goes with it.” (Atna / Brian George)

The process may be working for other people, but that’s for them to say. … Lands and resources are being negotiated away, access to our traditional territories are diminishing through resource development, rights are taken away that are entrenched in the constitution and that are recognized in Delgamuukw-Gisdayway 1997. The rightful hereditary people who have rights and title to the land are not being consulted. Consulting with the wrong people is a fast track strategy to resource development, and a resource grab for the ‘sell-outs.’ We need to survive in the new economy and are by no means looking to stop progress, but it’s got to be done in a respectful manner so our kids and grandkids…..We have to survive. We survived thousands of years. We’re going to continue to survive. Well, we have to have a say in it. (Greg George)

What is the legacy of Delgamuukw v. The Queen? Earlier this year, a bronze statue of the late Chief Justice Allan McEachern, who died in 2008, was installed in the Great Hall of the Law Courts in downtown Vancouver. And suicide among the youth of Indigenous Nations occupied by Canada outstrips the national average by eight times.

References:

You’ve Got to Paddle Your Own Canoe: The effects of federal legislation on participation in, and exercising of, traditional governance while living off-reserve, by Tsaskiy (Ron George), Department of Educational Psychology and Leadership Studies, University of Victoria, December, 2017

Delgamuukw v. British Columbia, [1997] 3 S.C.R. 1010

Colonialism on Trial: Indigenous land rights and the Gitksan and Wet’suwet’en sovereignty case, Don Monet and Skanu’u (Ardythe Wilson), New Society Publishers, 1992

North at Trent 2015 Lecture Series with Peter Grant, youtube, by TrentFostCtr, 2015

And special thanks to Chief Na’Moks, Wet’suwet’en, and Jack Woodward for fielding a few questions about the impacts of the case.

See also the statement of the Gitwangat Chiefs, 1884.

The site for the Vancouver local of The Media Co-op has been archived and will no longer be updated. Please visit the main Media Co-op website to learn more about the organization.