STORY about Indigenous posted on June 29, 2014 by Kerry Coast

UN report misses the mark on Indian Residential Schools Settlement Agreement, Truth and Reconciliation Commission

There was not “indigenous participation” in creating them.

Chief Wilton Littlechild, Ermineskin Cree was both a Commissioner with Canada's Truth and Reconciliation Commission, and a member of the UN Expert Mechanism on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples.

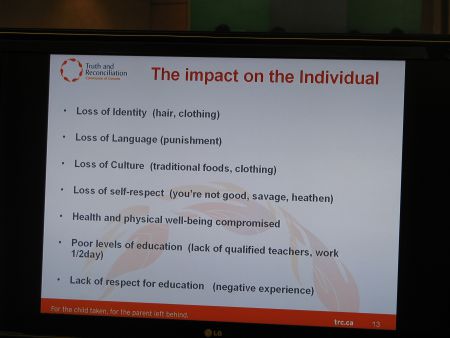

Chief Littlechild’s summary of the impacts of Indian Residential Schools on the individual are peculiarly silent on the loss of parents who were often driven to distraction by the loss of their children, or to returning to their communities being unable to communicate with their Elders, or the effect on the individual of the dissolution of the entire community into symptoms of post-traumatic stress disorder, or the collapse of the traditional economy once children were removed from it.

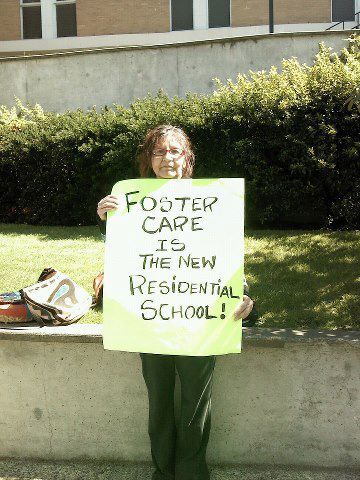

Seizure of Indigenous children and placement of them with non-indigenous families in Canada occurs at a rate 8 times higher than the Canadian average removal of children from their homes.

Also posted by Kerry Coast:

Also in Indigenous:

In response to the report of the Special Rapporteur on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples on the situation of Indigenous Peoples in Canada, May, 2014

The first ever official visit of a UN observer on the situation of Indigenous Peoples in Canada reported briefly on “…the ongoing implementation of the Indian Residential Schools Settlement Agreement, which was negotiated and agreed upon by former students, the churches that ran the schools, the Assembly of First Nations, other aboriginal organizations, and the Government of Canada.”

In the past four years, the Settlement Agreement has been meaningfully mischaracterized in United Nations forums on Indigenous Peoples. Extravagant statements by indigenous politicians produced in Canada have now found their way into this year’s extremely important report by the UN Special Rapporteur on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples. Those statements have apparently curtailed adequate investigation by the international observer, and have certainly supplied misinformation.

Official UN documents produced by Grand Chief Edward John, Carrier, in his role as a member of the Permanent Forum on Indigenous Issues, and presentations by Chief Wilton Littlechild, Ermineskin Cree, in his role as a member of the Expert Mechanism on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples, threaten to lead history on a detour away from the mass grave of unremedied crimes which is the Indian Residential Schools Settlement Agreement, or IRSSA. Littlechild and John are themselves former students of Indian Residential Schools. John has been the Chair of the First Nations Summit, the aboriginal party to the BC Treaty Commission, for twenty years. Littlechild has been one of three Commissioners of Canada’s Truth and Reconciliation Commission since 2009.

It is time to review the facts of the 2006 Settlement between the churches who ran the Indian Residential Schools and victimized the Indigenous children, the government of Canada which paid for the schools and criminalized parents who tried to keep their children home and employed Royal Canadian Mounted Police to return runaway children to the schools, and the national chief of the Assembly of First Nations who signed it on behalf of former students without soliciting a mandate or their participation.

The circumstances surrounding the Assembly of First Nations’ decision to enter a negotiating process with the Canadian government deserves illumination. For instance, existing legal actions by individuals and groups of former students against Canada and the churches in 2005 were estimated at 100 years’ worth of trial. Victims of the schools who had won in court were being awarded damages approaching the million dollar mark. The judges in the existing cases, some 3,300 of them involving alleged serious abuse, gave judgment accepting the IRSSA contract in settlement of the actions, and stipulating in its Schedule n for the creation and the jurisdiction of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission.

The indemnification objectives which were realized by Canada in the Settlement – that no former student who benefitted by the Agreement, or his family, could ever sue in connection to the Schools – were realized cheaply. The Settlement Agreement was foisted on the Survivors as an ultimatum: if too many people dropped out, 5,000 or more, no one would be paid at all and the two-year period between the Agreement in Principle and the deadline to opt out would simply be lost time for the cases that were already in progress. The Agreement then closed the door to court action against church or state by anyone who had lost their “language, culture and family life,” by asserting that the matter had been lawfully concluded by the government’s posting of public notices of its intention to do so and advertising the details. The advertising was delegated to the AFN and their categorical failure to communicate is documented below. The content of the Settlement was questionable, in particular the spectacular shortage of funding to meet the stated aims and benefits to Survivors of the schools and their families and future generations. The impacts of the lump-sum compensation payments to former students have been studied: the impacts were in many cases tragic.

The statement that this Settlement was “negotiated and agreed upon by former students” is wrong.

There is also nothing “ongoing” about the IRSSA, except its shadow. Federal funding for language and culture has dried up and blown away since former students accepted the Common Experience Payments and released Canada for “loss of language, culture and family life.” The small compensation received has been spent, and life is mostly back to the way it was except that there are many brand new trucks sitting, without insurance or gas, outside the dilapidated houses described in great detail by the Special Rapporteur in his report on Canada. Former students are entitled to a set number of clinical counselling sessions without charge, but access to traditional healing services is less certain.

The fact that Canada is still sacrificing the Indigenous Peoples and their lands to Canadian industry has not been remedied by the Settlement Agreement or the Truth and Reconciliation Commission, which was just extended for one year – but this fact today was inarguably made possible by the Indian Residential Schools century.

Manufacturing the false identity of the Indian Residential Schools Settlement Agreement, and Canada’s Truth and Reconciliation Commission

How is it possible that a report on the situation of Indigenous Peoples in Canada, so careful and thorough in most other areas, could fail to remark on the inadequacies of the Settlement Agreement, the Truth and Reconciliation Commission, and the resulting outstanding nature of the crimes of Indian Residential Schools?

The matter has been closed by people in high places; the paragraph about an “ongoing” program “which was negotiated and agreed upon by former students” is a poison which has already contaminated several streams of United Nations thought on this matter. That poison was administered by indigenous politicians from Canada.

Statements made in a study authored by Grand Chief Edward John for the UN Permanent Forum on Indigenous Issues describe the Settlement, for the first time anywhere in connection with discussion of the IRSSA, as “reparations.” This is an impossible demand on the definition of reparations. Compensation was made to individuals who were alive in 2005, while the crime of Indian Residential Schools was carried out against whole peoples for a century.

In the study’s conclusions, it remarks that: “The commissions have also proposed measures to repair the harm inflicted on indigenous peoples and establish mechanisms to help them realize their human rights to the fullest.” That blanket statement regarding all the Truth Commissions reviewed in the study most certainly does not stretch to cover Canada’s Commission, and yet there it is.

An impromptu presentation on the Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada, part of the IRSSA, was made by Chief Littlechild during the 2013 meeting of the Expert Mechanism on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples in Geneva. Littlechild was chairing the meeting and simply burst out with an unscheduled, hour-long power point one morning. He is also one of Canada’s TRC Commissioners. He showed slides to the indigenous delegates to the themed meeting on access to justice for indigenous peoples that had the appearance of an accountability report: “What the Commission has done so far to discharge its obligation;” “National Events;” “Research;” “Missing Children Project.”

In its placement at the start of a day of discussions on “access to justice” in the Human Rights Council Chambers in UN headquarters in Geneva, the presentation created the impression that Canada’s Truth and Reconciliation Commission was an example of access to justice – as one of the slides was titled. Canada could not have bought better credibility with money. Littlechild’s action of hijacking a UN meeting to glorify a state process was met with strained belief by the indigenous delegates. The presentation did not describe any moments of justice – just the activities of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission, such as commemorative events and a report on how many children died in Residential Schools.

Canada’s Truth and Reconciliation Commission has no power to subpoena perpetrators named during its collection of testimony from former students. The mandate specifies the Commission:

“shall not hold formal hearings, nor act as a public inquiry, nor conduct a formal legal process; shall not possess subpoena powers, and do not have powers to compel attendance or participation in any of its activities or events.”

“…shall perform their duties …in making their report and recommendations without making any findings or expressing any conclusion or recommendation, regarding the misconduct of any person, unless such findings or information has already been established through legal proceedings, by admission, or by public disclosure by the individual. Further, the Commission shall not make any reference in any of its activities or in its report or recommendations to the possible civil or criminal liability of any person or organization, unless such findings or information about the individual or institution has already been established through legal proceedings…”

**use slide “impact on the individual** and caption: Chief Littlechild’s summary of the impacts on the individual are peculiarly silent on the loss of parents who were often driven to distraction by the loss of their children, or to returning to their communities being unable to communicate with their Elders, or the effect on the individual of the dissolution of the entire community into symptoms of post-traumatic stress disorder, or the collapse of the traditional economy once children were removed from it.

Canada’s Truth and Reconciliation Commission is not on a mission for justice. In a brief produced by Dr. Bruce Clark, a legal expert on the Indigenous situation in Canada: “This is not only an expensive fraud upon the public but a cruel imposition upon the victims, who are encouraged to air their innermost suffering in the mistaken belief that it will lead to closure. The commission itself recognizes its task is only, "to document the truth of survivors, their families, communities and anyone who has been personally affected by the Indian Residential Schools legacy." The commission will look at symptoms but neither the cause nor the liability of the causer. It can not and will not investigate crimes by the government.”

If the natures of the Settlement and Commission are skewed now in international human rights circles, they are perhaps even less clear in Canada. In an example of the many mixed messages from Canadian media concerning the scope of the TRC, The Globe and Mail newspaper reported on January 1, 2008:

Former students plan to allege criminal deaths took place at Indian residential schools when they appear before a Truth and Reconciliation Commission, and the RCMP has been told to be ready to investigate.

Commission chief Bob Watts said he has met three times with police in the past year to advise them on the accusations former students are preparing to make. His comments mark the first time a senior official has acknowledged allegations deadly crimes were committed at the schools and that many children were buried without their parents being notified.

Mr. Bob Watts said he has been told that incidents of children disappearing at the schools were "quite widespread," but that there probably are few, if any, records.

"If a child didn't come back home because of something that was criminal, for example, it's probably not going to be in any records," he said. "We've heard stories about children being so severely punished, for example, that they died. So the commissioners are going to have to sort through how they are going to tackle this."

Mr. Watts said former students will also speak of deaths caused by criminal negligence, such as placing healthy children in dorms with those fighting infectious diseases such as tuberculosis.

An RCMP spokeswoman confirmed yesterday that police are "working very closely" with Mr. Watts but declined further comment until the commissioners are in place.

Mr. Watts said many of the accused will likely be dead. As a result, native elders are requesting the commission include some form of ceremonial activity to acknowledge any crimes that went unpunished.

Unfortunately, the 2014 UN report on the situation of Indigenous Peoples in Canada recommends an extension of the timeframe of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission – not an extension of its mandate to coincide with informing legal investigation of accused criminals.

Dr. Bruce Clark continued, “…It is specifically crimes or lesser wrongdoings "by a government" that such commissions, if genuine, exist to expose, as the precondition to reconciliation based upon truth.”

“Truth and reconciliation commissions in the Americas” was an agenda item for the UN Permanent Forum on Indigenous Issues at their annual meeting in May, 2013, at UN Headquarters in New York City. It was then that the study co-authored by Grand Chief John was released. The Permanent Forum’s study relied on Chief Littlechild as an expert witness.[i] The report described compensation to individual former students under the Indian Residential Schools Settlement Agreement as “reparations.”

A dozen people signed up for the speakers’ list to make interventions on the agenda item, delivering a printed copy of their statements ahead of time. When it came time for that agenda item, the Chair announced that there would be no space for the item to be responded to. He eliminated the speakers’ list – but allowed three: Wilton Littlechild; Edward John; and Eduardo Gonazalez from the International Center for Transitional Justice, who assisted Canada in developing its Commission. Their statements were a pinion of praise for Canada’s Commission. Chiefs John and Littlechild repeated themselves on the points that Indian Residential School survivors were active in the development and signing of the Settlement Agreement, which formed the TRC; that those processes have announced a positive breakthrough in Canadian society; and that the Truth and Reconciliation Commission is equivalent to justice in progress. They always remark or infer that Indigenous Peoples throughout Canada are very satisfied with the Commission’s work so far, and that it signals the end of a colonial epoch.

Delegates and even the translators at the PFII meeting noted how unusual it is for an agenda item to be denied intervention without notice, even after a speakers’ list has been populated and print copies provided for translators. One of the excluded interventions read,

The IRSSSA and TRC as launched by the Canadian government, however, was a process which sought to extinguish Indigenous Nations’ right to reparations without acknowledging the full dimension of the crimes (genocide, crimes against humanity, forced assimilation) committed against them. Instead it offered individual claimants compensation for personal injuries and abuse, establishing a ceiling limit for payments, and required a written “opt-out” procedure for those who spurned such paltry acknowledgements of the vastness of the damages visited not only upon themselves but upon their nations. Many who accepted the compensation payments were not informed of their legal rights by the state-funded counsel which uniformly advised them to do so. [ii]

The Permanent Forum’s study gives this description of the Canadian Settlement Agreement and its mandate for the TRC:

The Commission grew out of a lengthy process of disputes and court-mediated negotiations that resulted in an extensive programme of reparations and a request for a formal apology from religious and State institutions that had acted in complicity in those abuses. In 2006, following extensive negotiations between the Government, churches and indigenous peoples, the Canadian Government approved the Indian Residential Schools Settlement Agreement, which cost an estimated 2 billion dollars. The Agreement called for the establishment of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission with a portion of the funds earmarked for reparation.

There were no “extensive negotiations between the Government, churches and indigenous peoples.” The statement is a lie with extreme implications, since the mark of an acceptable settlement of this type is the full and informed participation of Indigenous Peoples in creating it. By reporting that the Settlement Agreement met this criteria, Grand Chief John has single handedly elevated the Settlement and the Commission to a place it is not worthy of.

The study relied on statements made by Chief Littlechild, and Chief John named him as an expert witness when introducing the study during the Permanent Forum’s 12th Session, in 2013.

Chief Littlechild also made an intervention to the Expert Mechanism on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples before he became a member of it, in 2010, but when he had just been named to the Truth and Reconciliation Commission:

“…this TRC was not created by the government. Rather it was established as an independent body with a 5-year mandate through the efforts of residential school survivors themselves as part of the largest class action lawsuits in Canadian history.”[iii]

On the contrary. Professor Kathleen E. Mahoney, a non-native lawyer, was the Chief Negotiator for the Assembly of First Nations in achieving the Indian Residential School Settlement Agreement. She was also “the primary architect of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission and led the negotiations for the historic apology from the Canadian Parliament and from Pope Benedict XVI at the Vatican," according to her online biography.

Furthermore, in April of 2008, the Canadian federal public service civil list was amended to add the Commission and its entourage of lawyers, researchers and consultants to the federal payroll.

Lies and insinuation heaped on misrepresentation have formed international reputations for the Settlement and the Commission which bear no resemblance to the facts. Instead, those lies from the top of the world’s most influential organization have deafened an official visitor to the voices of the people who travelled hundreds of miles to tell him the truth while he was visiting Canada.

The shadows of the Indian Residential Schools Settlement Agreement:

in the shadow of the myth of former students’ participation in developing the Settlement Agreement and the Truth and Reconciliation Commission

It seems that when statements are made to the effect that former students were involved in negotiating the contents of the Settlement Agreement, they refer to former student Phil Fontaine, then Chief of the Assembly of First Nations which claimed leadership of what they called a “class action.” It is important to remember that the AFN is entirely subsidized by the government of Canada.

At a single AFN conference to discuss the Settlement in Winnipeg, in May of 2007, after it had been announced in its final form and approved by the government of Canada late in 2006, National Chief Phil Fontaine spent all his speaking time defending the Agreement without actually describing what it included. He was defending it to a lot of people who did not seem very impressed, and all expressed shock at the content – not a signal that any of them had participated in creating it or had heard from someone who did. Participants at that meeting included some of the most credible Indigenous leaders. The fact that none of them were involved in the negotiations of the Settlement is revealing. "This Settlement Agreement was not handed to us on a silver platter. We had to fight for every little bit that's in the Agreement," said Fontaine. But every part of the Settlement Agreement was the lowest common denominator of what Canada had already offered claimants in class action suits, and which those former students had rejected.[iv]

The AFN did produce a press release in response to frequently asked questions, dated November 23, 2005. It begins: “The AFN played a key and central in achieving the Agreement in Principle signed on November 20, 2005 to settle all Indian Residential School claims.” This sentence is copied directly from the press release; we are not sure what noun might be described by “key and central,” but the statement in unequivocal. It was not former students, but the AFN which was central to the Agreement.

This is confirmed in the opening of the next paragraph: “The biggest and most important victory the AFN was able to obtain for survivors in the Settlement Agreement is a new form of compensation for loss of language and culture and loss of family life through a lump sum payment or common experience payment (CEP) as it is called in the Agreement.” In this, the Assembly’s first press release on the subject of the Agreement in Principle for the Settlement Agreement, they do not mention “extensive negotiations between the Government, churches and indigenous peoples.” If those negotiations were a historical fact, the AFN would have mentioned it and recognized the people involved. But it is not a fact, it is a lie. The AFN was the key indigenous organization involved, they did not have a mandate to represent former students because former students do not vote in AFN assemblies – only Band Council Chiefs do, and Band Councils across Canada did not hold referendums seeking this mandate from their communities.

There are many more sources who attest to the absence of former students in creation of the Settlement and the Truth and Reconciliation Commission which was mandated within it by the judges who turned their plaintiffs over to it. Bob Watts was the CEO of the AFN at the time of negotiations. He recalled the development of the Settlement this way, during his talk at the 2012 Vancouver Human Rights Lecture:

National Chief Fontaine put together a proposal to look at a negotiated settlement. With the Assembly of First Nations we entered the process with lawyers from class actions from across the country - some representing individual survivors, lawyers representing churches, government, other aboriginal organizations.

Note that “other aboriginal organizations” tend to defy specific description in such testimonies as this presentation by Watts. And that an “aboriginal organization” is not a people. The harms of Indian Residential Schools were done to peoples. Watts continued:

I remember one time we were in Calgary. We were having a break and I was outside talking with one of our Elders who was part of our team, I asked him, how do you think things are going in there? And he said, “did you ever see that movie about Nemo?” “Finding Nemo? Yeah.” “You remember the seagulls?” “Yeah, I remember.” “That’s what they’re doing in there: ‘mine, mine mine mine mine,’ all the time. That’s what’s going on in there. Where are the Residential School survivors? They need to be first and foremost in everybody’s mind or we’re not going to have a successful negotiation.”

So we made sure the National Chief knew about that and it actually changed the dynamic of the negotiations.

The Assembly of First Nations, through National Chief Phil Fontaine, ended up launching its own class action to ensure a seat at the table* and be able to speak to every significant issue.

*Emphasis added.

An interested observer of the process corroborates this report another way. Having just won in court against the church that ran the school where he was sexually abused, and won damages worth “seventeen times the average common experience payment, if the average payment is $30,000” under the Settlement Agreement, William Blackwater wrote several letters to the Canadian Minister of Indian Affairs concerning the Settlement, in 2009.

Some suggest that there are survivors at the tables, but if you observe them for a few moments you will see that these are also our political leaders; leaders with other agendas. They are leaders with other motivations. They are NOT the survivors that receive the chronic abuse. They are not survivors that are facing the challenges of the legacy. To them we say great, you have moved on, but some of us have not had that opportunity. Please give us the same chance. We know that you have had space at the table and we are asking the same opportunity: we face the consequences of the Indian Residential Schools legacy every day without power, money and resources.

I am frustrated and continue to be concerned that my leadership and our decision makers do not take seriously survivor concerns. It is evident in the lack of involvement of survivors; it is evident in the Truth and Reconciliation Commission Commissioner selection; it is evident in the implementation of the TRC; the implementation of the Independent Assessment Process, and the list goes on. [v]

Blackwater was for many years involved in the leadership of the Indian Residential Schools Survivors Society, a group based in British Columbia. He said in an interview with The St’át’imc Runner newspaper, in September 2007, “The AFN said they launched that suit on behalf of all survivors in Canada. When we went to the National Residential Schools Survivors Society national meeting in 2007, not one regional director was aware of a single survivor that had given their consent for Fontaine to act on their behalf in regard to the CEP package. None of us knew anything about it until after the fact.”

Bob Watts was also the AFN’s deputy at work with the government designing the Truth and Reconciliation Commission. He went on during his Vancouver lecture to give the only evidence of engagement with former students during the process of developing the Commission:

We were fortunate in terms of designing the Truth and Reconciliation Commission of having help from other TRC’s, sister truth and reconciliation commissions from around the world. One of the really important things we learned from the International Center for Transitional Justice was that we needed to manifest the outcomes that we sought to achieve. So that became the watchword for all of our work.

When we did dialogues all across the country and met with survivors about what they wanted to see from the Truth and Reconciliation Commission, that was our watchword.”

What Watts is describing here is a sort of legalistic consultation process led by the AFN. Judging by the complaints of leaders among advocates for former students, that consultation was obviously extremely limited and occurred late in the development of the Commission. This is probably not what most people would expect to hear when they are being told Canada’s Truth and Reconciliation Commission was “led by Survivors,” as Chiefs John and Littlechild repeatedly say.

in the shadow of the absence of informed consent

The Assembly of First Nations made millions from Canada just in its fee for (not) delivering the communications requisite to properly carrying out the consultative and consensual criteria demanded by the Settlement Agreement and its opt-out condition. The Agreement was subject to an opt-out action: if more than 5,000 former students formally opted out of benefits under the Agreement, it would be nullified. Well-paid delegates of the AFN visited a few communities but left again without having imparted the real crux of the matters contained in the Settlement, according to participants. Friendship Centers across the country eventually used their own resources to hold information sessions and study the Agreement.

By the time the opt-out deadline had passed, former students’ confusion about the process was certainly clear to the Empowered Residential School Survivors. This group of volunteers, based in the Nlaka’pamux nation in the interior of British Columbia, created a DVD called “Prep for CEP.” The presentation was a collection of interviews with lawyers, accountants and clinical councilors who offered analysis of the process and anticipated matters that would arise for former students participating in it.

The National Residential Schools Survivors Society had, at the time of the AFN announcement of the Settlement process, a membership of some 8,000 former students from across Canada. Their Chair, Ted Quewezance, attended a three day meeting in Lytton, Nlaka’pamux, organized and funded by the Empowered Residential School Survivors volunteers in September of 2007:[vi]

What I want to talk about is this Agreement. Phil Fontaine says, "It's not perfect," and I agree with him. A lot of survivors think we should have gotten more.

There's a lack of participation by Survivors in this Agreement. Many Survivors don't know what's going on. It was supposed to be for Survivors, but Survivors don't have a say in this Agreement. We did three surveys, in Montreal, Ottawa and Edmonton. We have identified over 1,000 concerns and issues about this Agreement. We're not trying to kill the Agreement, it's too damn late. The implementation starts today - the train is leaving Ottawa, and the judges, the lawyers, the AFN, the politicians, they all have a seat on that train. But there's no Survivors on that train.

The deadline for former students, or their orphans or widows, to remove themselves from inclusion in the Settlement by formal notice, to “opt-out,” was August 20, 2007. Although it is safe to say that the majority of former students had no way of knowing about the significance of this clause, particularly widows and orphans of former students, or informed advice on what they should do, 1,074 former students opted out.

The fact that over 600 people attended the informational event in Lytton, BC, shows a lot of interest in questions that were not being answered by the AFN through their well-funded mandate to communicate the details of the Settlement. With a membership of 500 former students, the Empowered Residential School Survivors developed the September 2007 conference to help former students understand the meaning of the Settlement. Co-Founder Fred Henry explained the need for their action:

"We felt that all the information wasn't getting back to our people here. We went to the Winnipeg National Survivors' Conference. The conference was the start of our journey to help other Survivors and bring home and share what we learned. A lot of communities did not even know what the package consisted of, the Common Experience Payment, the Individual Assessment Process, the Opt-In Opt-Out period; what it all meant.

I know there are people out there who felt we are interfering with their programs. But we are not. We are grassroots people helping grassroots people. We are not politically driven in any way. We are holding this gathering for you. We are seeking healing across our nations.”

People left to rely on the AFN’s bulletins did not understand the “alive in 2005” condition. Spouses of deceased former students did not know they should have their children formally withdraw from the Agreement or be bound by it, even when neither they nor their loved one had benefitted by it. Children of deceased former students anticipated compensation. Most survivors knew they would never be able to sue for damages once the Settlement Agreement was passed unless they had opted out – but most did not know that in order to collect damages for gross physical abuses under the Settlement’s Independent Assessment Process, they would have to testify, to call witnesses, and to endure similar trial procedures to the court process that had deterred them from pressing their cases in the first place. They were also not given a comparison estimate of the difference in value of an independent court award for the most serious abuses and an award under the Independent Assessment Process (IAP) stipulated by the Agreement. The difference was 80-95% less in the IAP than similar damages awarded through the courts.

in the shadow of the myth of “reparations”

By 2012, the National Residential Schools Survivors Society had grown to 32,000 members. That February, the Society made a call for a judicial review of implementation of the Settlement Agreement. “The settlement agreement is an out-of-court settlement that is to be monitored by the courts," said chairman Ray Mason. "Yet each day we have survivors complaining about their treatment by a consortium of lawyers, the role of Canada, lost records, information not provided, adjudicators not respecting our culture or language. Why is the court not taking responsibility?"

“We, as survivors from every region across this country, are totally, totally frustrated,” declared Ted Quewezance, spokesperson for the Society, in the NRSSS press conference. “It’s really hard to reconcile when the perpetrators, the churches and government, are not even at our TRC events. I ask, how do we have reconciliation when the perpetrators are not in the room? Where is the Member of Parliament when these TRC events are going on? Where is the church? The intent of the TRC was to have seven national events and educate Canadians, and that is not happening. We would like to open a public dialogue with survivors, families and communities across the country on continuing acts of genocide perpetrated against our people.

In response to the NRSSS demand, a spokesperson for Canada gave her position that, "The IRSSA is a court-approved and court-monitored class-action settlement of all Indian residential school claims across Canada and does not include a requirement for an independent review.”[vii]

In April of 2014, as party to the Settlement Agreement, the Assembly of First Nations appeared in court to make the case that “survivors of Indian Residential Schools must be treated fairly and with dignity consistent with the spirit and terms of the Indian Residential Schools Settlement Agreement.” It seems that a high percentage of former students had been paying fees to lawyers and form-fillers in connection with their applications for compensation under the Settlement. A Manitoba Court decision this month, June 2014, determined that a large number of fee agreements invoiced to former students have been “illegal and unconscionable.”

The Independent Assessment Process was itself largely unconscionable.

Under the Settlement Agreement, adults who pursued their grievances of sexual assault while they were children in residential school were compensated according to a never before seen points-system model of assessment of harm. One rape, two rapes, 35 rapes; vaginal, oral, anal; one beating, five beatings, 60 beatings; all led to a sum of points which were then assessed at a uniform dollar value. The humiliation experienced by these adults at having to put forward their most painful personal losses, as if they could count them, in such hearings defies description. That is to say nothing of the revival of old wounds, the sense of injury, the sense of further victimization at agreeing to settle so low. Victims of sexual assault were compensated mainly in the order of 10% of settlements awarded in similar cases arrived at in individual suits against the schools as early as 1997.

The deadline for submissions under the IAP was September 19, 2012.

Victims of physical and mental abuse fared worse comparatively. Loss of income and loss of employability worked in favour of those who had lived all their lives after as alcoholics—and then quickly drank themselves to death after receiving their payments—but it worked against those individuals who did have the strength or unknown combination of support and luck to carry on. Two women who suffered the exact same abuses were awarded compensations varying by $50,000, the rationale given to the one who received a $16,000 pay-out for her complaint of several rapes being that she had managed to carry on a comparatively normal life: to hold down a job, raise a child and maintain a relationship.

Since the Settlement Agreement, funding to the Aboriginal Healing Foundation stopped in 2010. The Foundation was created in 1998, with a ten year mandate and initial funding of $350 million. Just before its untimely and tragic demise, not to be replaced, the Foundation released a study on the impacts of the lump-sum compensation to former students. Under the Common Experience Payment (CEP) aspect of the Settlement Agreement, former students were paid $10,000 for the first year they spent in an Indian Residential School, and $3,000 for each further year – the “10 + 3 formula.” This was an award for “loss of language, culture and family life.” The study’s findings included that “as of November 2009, Survivors had submitted 99,204 CEP applications. 74,701 payments were issued to Survivors, with the average payment being $20,529.” The deadline for CEP applications was September 19, 2011.

The report prepared for the Healing Foundation concluded the following based on intensive interviews in various locations across Canada:

Almost 20% of participants said that the CEP process and money were steps backward on their healing journeys. For these Survivors, the CEP process represented a very negative period in their lives and left them feeling worse off than before. They expressed bitterness and resentment toward an inadequate “10 plus 3” formula, anger toward eligibility criteria that deprived compensation to many living Survivors, and grief over the many Survivors who died before the Settlement Agreement was implemented.

About one-third of participants spoke about CEP and compensation from perspectives that took into account the intergenerational impacts of the residential school system. Survivors said the Common Experience Payment was not enough because the ongoing direct and indirect effects of the physical and sexual abuse that took place at residential schools cannot be compensated, and also that individual compensation is illogical in the sense that the residential school experience is not an individual phenomenon. It is a family and community experience that crosses generations.

The intergenerational issues most commonly raised related to family alienation which in turn resulted in a lack of parenting skills; however, participants also said that the CEP process led to increased openness between themselves and their children about the legacy of residential schools.[viii]

The study made reference to a dramatic increase in deaths within a year of the payments, but did not focus on the point. The study referred to suicides as individuals neared the time of an interview with government assessors of serious abuse in the Independent Assessment Process; death by overdose or intoxicated accident; and even murders, as events at the schools, long kept secret, began to come to light with victim testimonies in the Settlement-induced chaos.

Recently, the First Peoples’ Heritage, Language and Culture Council of the province of British Columbia has become the First Peoples’ Culture Council.” Heritage and Language are no longer specified. An Indian Residential School Survivor from Ts’k’way’lacw, St’át’imc territory predicted the dénouement in a 2008 interview. Rick Alec is a Native Alcohol and Drug Abuse Program Counsellor in Pavillion.

They squeezed the language and culture component into that agreement.

What's going to happen to the language programs we have on reserve now? I think it's going to affect all the programs. It might not show right off the bat, but it will come down later.

Five years from now you're going to ask for program funding for a language class, and they're going to tell you that's been dealt with in this settlement: compensation for loss of language and culture.

It's a turning point for us as native people, where we are either going to move forward or not. You hear it all the time: 'what's wrong with us started with the residential schools.' But after we take this money, there's no one left to blame. All the responsibility will be with us.

in the shadow of the myth of non-recurrence

When he goes on and on about truth and reconciliation at UN meetings in New York and Geneva, TRC Commissioner Chief Wilton Littlechild never mentions the modern day rate of apprehension of indigenous children and the placement of those children with non-native families. This is a kind of violent assimilation, actually fitting the description of Article 2 of the Genocide Convention, which carries on in spite of the Prime Minister’s apology to former Indian Residential School students where he promised such a thing would never happen again. In his 2012[ix] address to the Expert Mechanism on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples, contemplating the creation of the Access to Justice for Indigenous Peoples study, Littlechild mentioned the Special Rapporteur on Reparations and Non-recurrence in the same paragraph as thanking the government of Canada for financing his conference.

Indigenous children are seized from their families by Ministries of Child and Family Welfare at a rate eight times that of the Canadian average. The British Columbia Advocate for Children and Youth, Mary Ellen Turpel-Lafonde, has written a stack of reports on the shocking fates of too many of these children once in state care. The Attorney General of Canada has also written damning reports of federal agencies charged with the care of apprehended indigenous children.

The formal education of Indigenous children is another relevant matter, when considering the impact of Indian Residential Schools. Today, indigenous children must attend public school in Canada, whether on or off-Reserve, where the curriculum is controlled by the state. The UN Special Rapporteur on the rights of Indigenous Peoples’ 2014 report notes:

There are approximately 90 aboriginal languages spoken in Canada. Two-thirds of these languages are endangered, severely endangered or critically endangered, due in no small part to the intentional suppression of indigenous languages during the Indian residential school era. The same year the federal Government apologized for the residential school policy, 2008, it committed some CAN$220 million annually for the next five years to Canada’s “Linguistic Duality” program to promote English and French. By comparison, over the same period, the federal government spent under CAN$19 million annually to support indigenous language revitalization.

The report also summarizes indigenous objection to the unilateral federal First Nations Education Act:

Indigenous leaders have stated that their peoples have not been properly consulted about the bill and that their input had not been adequately incorporated into the drafting of the bill. The main concerns expressed by indigenous representatives include that (1) the imposition of provincial standards and service requirements in the bill will undermine or eliminate First Nation control of their children’s education; (2) the bill lacks a clear commitment to First Nations languages, cultures, and ways of teaching and learning; (3) the bill does not provide for stable, adequate, and equitable funding to indigenous schools; and (4) the bill will displace successful education programs already in place, an issue that was raised particularly in British Columbia.

in the shadow of “An Historic Non-apology”

Many former students found relief in the apology which Prime Minister Steven Harper delivered on June 11, 2008. There was finally recognition by the head of state that the violence which was done to them as children, their removal from their homes, was wrong.

Indigenous academics and lawyers found the formal statement bitter, however, and roundly criticized the government’s careful wording in place of something more honest. Dr. Roland Chrisjohn and five others jointly released the lengthy statement “An Historic Non-apology, completely and utterly rejected” from which the following is excerpted:

We doubt that the Conservative party didn’t have a team of lawyers, rhetoricians, and spin doctors, if not writing the statement, at least agonizing over every phrase, every word, every revelation in the evolving document, considering in detail every implication and weighing each possible consequence. We had no trouble seeing through the Prime Minister’s tortured prose because we’re well aware of related issues that are no part of what the average Canadian is supposed to know and what government and church officials know all too well: the United Nations Genocide Convention and Canada’s role in it...

Bringing genocide to the table would take the churches, but more centrally the government of Canada, into the exhaustive examination of additional regions of its policies and programs with respect to indigenous peoples, regions that, up until now, it has successfully avoided (or at least, as it is now trying to do with residential school, managed to isolate from other policies). And, what is perhaps even more important, establishing that Canada’s policies toward indigenous peoples constitute an historic and ongoing genocide rules out Mr. Harper’s statement as an apology, since such would violate the second feature of a genuine apology; someone who is still doing it can’t be promising not to do it again.[x]

As for the suspected team of lawyers and spin doctors behind the public apology, if they weren’t there at that point they certainly were there when it came time to devise a system through which survivors of physical and sexual abuse would be compensated. Consider the following testimony. A junior employee with the Department of Indian Affairs was offered a job description one day, in connection with this scheme to minimize the damage. Her supervisor explained that if she took the new position, there would be an immediate promotion for her within the Department, followed by a second promotion within the year. The job description was not allowed out of the supervisor’s sight, much less out of the office; she was not allowed to make a copy. The lucky candidate, a sharp young woman fresh off the job of surveying and reporting on the state of native court services in Saskatchewan, chosen especially because she herself had Indian Status, had to read the job offer and return it immediately.

She had been hand-picked for the job of working in a team to find ways to minimize payments to Settlement claimants. Chantal Perrault left the Department then and sought out organizations that were actually attempting to advocate for indigenous peoples.[xi]

The report of the Special Rapporteur on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples on the situation of Indigenous Peoples in Canada, May, 2014

In spite of the untrue phrases written by others and copied into the Special Rapporteur’s report, some paragraphs will vindicate the victims of Indian Residential Schools, the Indigenous Peoples, better than the Indian Residential Schools Settlement Agreement and the Truth and Reconciliation Commission combined:

5. A particularly distressing part of the history of human rights violations was the residential school era (1874-1970s, with some schools operating until 1996), which destroyed their family and even their names. Thousands of indigenous children did not survive the experience and some of them are buried in unidentified graves. Generations of those who survived grew up estranged from their cultures and languages, with debilitating effects on the maintenance of their indigenous identity. This estrangement was heightened during the “sixties scoop” during which indigenous children were fostered and adopted into non-aboriginal homes, including outside of Canada. The residential school period continues to cast a long shadow of despair on indigenous communities, and many of the dire social and economic problems faced by aboriginal peoples are linked to that experience.

31. With respect to other issues affecting the well-being of indigenous peoples in Canada, among the results of the residential school and “sixties scoop” eras and associated cultural dislocation has been a lack of intergenerational transmission of child raising skills and high rates of substance abuse. Aboriginal children continue to be taken into the care of child services at a rate eight times higher than non-indigenous Canadians. Further, the Auditor General identified funding and service level disparities in child and family services for indigenous children compared to non-indigenous children, an issue highlighted by a formal complaint to the Canadian Human Rights Tribunal by the First Nations Child and Family Caring Society and the Assembly of First Nations. In a positive development, in 2000 the Province of Manitoba and the Manitoba Métis Federation, which represents Métis rights and interests in the province, signed a memorandum of understanding for the delivery of community-based and culturally appropriate child and family services, which has demonstrated important successes.

88. The Government should ensure that the mandate of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission is extended for as long as may be necessary for it to complete its work, and should consider establishing means of reconciliation and redress for survivors of all types of residential schools.

[i] Study on the links between indigenous rights, truth commissions and other truth-seeking mechanisms on the American continent (Etc.t9t20t3lt3) 28 May 2013

[ii] Intervention submitted by delegate of the International Human Rights Association of American Minorities.

[iii] United Nations Human Rights Council 15th Session, September 13 – October 1, 2010, Palais de Nations, Geneva Intervention by Chief Wilton Littlechild, Commissioner, TRC of Canada, Agenda Item 5: report of the UN Expert Mechanism on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples

[iv] The grass-roots organization “Empowered Residential School Survivors” drove from points in BC to the conference, video recorded it, and distributed copies in DVD format.

[v] Open letter to Minister of Indian and Northern Affairs Canada, Chuck Strahl, February 16, 2009. “Re: TRC Protocol and Process”

[vi] Empowered Residential School Survivors, Information and Healing Gathering, Lytton, BC, September 19, 20, 21, 2007, “Healing Through Empowerment.”

[vii] Winnipeg Free Press - PRINT EDITION “Residential schools pact needs review: coalition - It's not going to happen, federal government says” By: Alexandra Paul Posted: 02/3/2012

[viii] The Indian Residential Schools Settlement Agreement’s Common Experience Payment and Healing: A Qualitative Study Exploring Impacts on Recipients. Prepared for the Aboriginal Healing Foundation, 2010

[ix] Statement by International Chief Wilton Littlechild, Expert Member (WEOG Region) 6th Session of the UN Expert Mechanism on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples (8th-l2th July 2013) Agenda Item 5: Study on the Access to Justice in the Promotion and Protection of the Rights of Indigenous Peoples July 9th', 2012

Good afternoon to all delegations. Our custom at the Expert Mechanism has been to hold an International Expert Seminar on the subject of our primary study each year, in order to receive the benefit of input from knowledge holders, academic thinkers and experts in the area. This year, we held the International Expert Seminar on Access to Justice for Indigenous Peoples, including Truth and Reconciliation Processes at Columbia University. We would like to thank the hosts and co-organizers, the Institute for the Study of Human Rights, the international Center for Transitional Justice and the Office of the UN Commissioner for Human Rights. We were particularly pleased to hear from Mr. Pablo de Greiff, Special Rapporteur on the promotion of truth, justice, reparation and guarantees of non-recurrence provide a keynote address. We would like to thank all the speakers of the International Expert Seminar, a few of whom are present here today. We would also like to thank the government of Canada for their financial support of this Seminar.

[x] An Historic Non-Apology, Completely and Utterly Not Accepted, By Dr. Roland Chrisjohn, Professor Andrea Bear Nicholas, Karen Stote, Professor James Craven (Omahkohkiaayo i’poyi), Tanya Wasacase, Pierre Loiselle, and Andrea O. Smith.

[xi] The Colonial Present, the rule of ignorance and the role of law in British Columbia, by Kerry Coast, Clarity Press, 2013.

The site for the Vancouver local of The Media Co-op has been archived and will no longer be updated. Please visit the main Media Co-op website to learn more about the organization.