STORY about Indigenouspublié le Juin 27, 2014 by Kerry Coast

Aboriginal title lands recognized in Canada

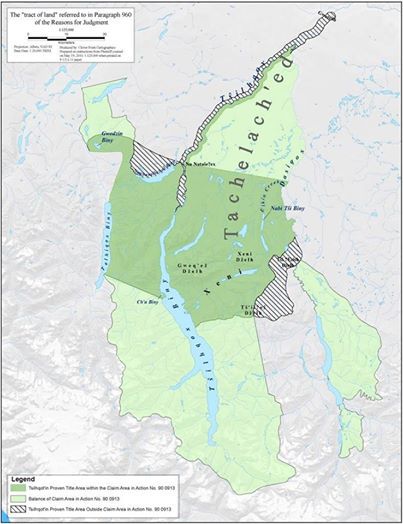

Chief Justice defines aboriginal title in a ruling on the Tsilhqot'in action for a declaration of aboriginal title.

Also posted by Kerry Coast:

Also in Indigenous:

In 1989, the Tsilhqot’in people stopped foreign-owned logging operations in their Brittany Triangle. The argument over logging carried them through courts, where the provincial and then the federal governments insisted that it was perfectly legal to license logging operations under the provisions of BC’s Forestry Act. That’s why, when Chief Roger William and the Tsilhqot’in Nation launched an action against Canada, they argued that the provincial Forestry Act could not apply in the area because these were aboriginal title lands – not crown land.

The Tsilhqot’in have their declaration of aboriginal title lands. It is the only place in Canada which is recognized as such. Aboriginal title has never been recognized on the ground, with an address; and until this time the governments have acted as if it were a hypothetical concept.

Chief Justice Beverly McLachlin wrote the reasons for the unanimous decision and has given much definition to aboriginal title. She has said that it will be treated the same as “lands reserved for the Indians,” under the Canadian constitution. She said it doesn’t make sense that the provincial forestry regulations should not apply on aboriginal title land, because that would be inconvenient. She notes that both the federal and provincial governments are happy to allow the province to keep regulating over “lands reserved for the Indians,” which now includes aboriginal title lands, even though it is a strict division of powers in the Canadian constitution which forces only the federal government to have power over “Indians” and their lands.

The federal government does not have a forestry act. The Tsilhqot’in do. However, the ruling was written for the governments, as if the Tsilhqot’in people had played their part by raising this question of interjurisdictional immunity between the federal and provincial powers, and now that the question has been answered they can go back to being “consulted” and “accommodated” as to whether activities carried out under the Forestry Act are infringing their rights. Now, with title, the court has called their rights in the title area "the right to proactively use and manage the land.” The BC Forestry Act applies insofar as it does not infringe Tsilhqot'in aboriginal rights, now including their aboriginal title.

The Supreme Court has decided that provincial laws of general application are in effect on aboriginal title lands, excepting where "the limitation imposed by the legislation is unreasonable; the legislation imposes undue hardship; and the legislation denies the holders of the right their preferred means of exercising the right.”

The governments view aboriginal title as a form of aboriginal right. Indigenous Peoples in general view their rights as a function of their titles: they are the peoples of the land, their rights to it and to their own governance flow from that fact. The Canadian approach removes the connection between the peoples and the lands, saying effectively that modern aboriginal rights are provided by the grace and recognition of Canada, not by the lands and waters which reflect millennia of title and free exercise of rights.

The question which was trying to be asked is therefore also one of jurisdiction. If the Tsilhqot’in are declared by the highest Canadian court to be living on lands which they hold aboriginal title to, that was expected to change what form of governance occurs on those lands. McLachlin has said it doesn’t change anything about governance, except:

"In summary, Aboriginal title confers on the group that holds it the exclusive right to decide how the land is used and the right to benefit from those uses, subject to one carve-out — that the uses must be consistent with the group nature of the interest and the enjoyment of the land by future generations. Government incursions not consented to by the title-holding group must be undertaken in accordance with the Crown’s procedural duty to consult and must also be justified on the basis of a compelling and substantial public interest, and must be consistent with the Crown’s fiduciary duty to the Aboriginal group."

The significance of this passage is that it is saying two things which cannot both be true. If people who have aboriginal title can exclusively decide how land is used then it can’t also be that Canada can decide to infringe on that power when it has a “compelling and substantive” reason based on the interests of Canadians.

It is a continuation of a Delgamuukw decision that land use by aboriginal people can’t jeopardize the future of the people, and that Canada can infringe aboriginal rights if it has a “compelling and substantive” reason to do so. Examples of justifications for infringing aboriginal rights include, according to the 1997 Delgamuukw judgment: hydroelectric development, mining, oil and gas exploration. It was Delgamuukw that first began to describe what aboriginal title means, and it included the following, confirmed in this judgment: “the right to exclusive use and occupation of the land; the right to determine the uses to which the land is put, subject to the ultimate limit that those uses cannot destroy the ability of the land to sustain future generations of Aboriginal peoples; and the right to enjoy the economic fruits of the land.”

The June 26, 2014 ruling has reserved to Canadian courts the right to decide what aboriginal title means, presumably at their convenience:

This case has put aboriginal title in place along with all aboriginal rights: it is controlled and regulated by Canada; interpreted and defined by Canada; it can be infringed by Canada and by the provinces. Aboriginal title land can only be alienated, or sold, to the crown.

The legal elevation of aboriginal title is defined in paragraph 91:

“…prior to establishment of Aboriginal title, the Crown owes a good faith duty to consult with the group concerned and, if appropriate, accommodate its interests. As the claim strength increases, the required level of consultation and accommodation correspondingly increases. Where a claim is particularly strong — for example, shortly before a court declaration of title — appropriate care must be taken to preserve the Aboriginal interest pending final resolution of the claim. Finally, once title is established, the Crown cannot proceed with development of title land not consented to by the title-holding group unless it has discharged its duty to consult and the development is justified pursuant to s. 35 of the Constitution Act, 1982.”

The trouble with the legal process of justifying infringement of aboriginal rights, with waiting helplessly until “the government has discharged its duty,” is that the government has a proven track record of doing the damage first and then only later are they taken to court to prove what happened. So if the government does not comply with “its procedural duty to consult with the rights holder and accommodate the right to an appropriate extent at the stage when infringement was contemplated;” or is unable able to show that “the infringement is backed by a compelling and substantial legislative objective in the public interest;” or fails to determine that “the benefit to the public is proportionate to any adverse effect on the Aboriginal interest” – we will have to wait until the damage is done and a Canadian court reveals the answer.

The UN Special Rapporteur on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples recently remarked on the consultation and accommodation practices in Canada, “However, the indigenous representative with whom the Special Rapporteur met expressed concern that, generally speaking, provincial governments do not engage the duty to consult until development proposals have largely taken shape. When consultation happens, resource companies have often already invested in exploration and viability studies, baseline studies are no longer possible, and accommodation of indigenous peoples’ concerns requires a deviation from companies’ plans. The Special Rapporteur notes that this situation creates an unnecessarily adversarial framework of opposing interests, rather than facilitating the common creation of mutually beneficial development plans.”

The ruling found that the province had unjustifiably infringed the Tsilhqot'in aboriginal rights when it authorized logging in the title area; the province shares the same duties to aboriginal peoples on aboriginal title lands that the federal government does, with respect to consultation and accommodation. A great deal of clearcut logging has impacted the title area, so there is good cause for further litigation by the Tsilhqot'in for damages.

The Supreme Court held that “After Aboriginal title to land has been established by court declaration or agreement, the Crown must seek the consent of the title-holding Aboriginal group to developments on the land.”

The test for proving aboriginal title has, for the first time, been completed. An aboriginal people must prove continuing and exclusive occupation, and now there is a precedent for doing that. It took the Tsilhqot’in 339 days of trial over five years, with a judge who visited them in their lands, attended night court there, and went so far as to create his own map of the title area.

This is what the Special Rapporteur on the rights of indigenous peoples, James Anaya, was talking about when he described in his recent report on Canada the disingenuous and humiliating approach the state takes in beginning negotiations with Indigenous Peoples: “In the comprehensive land claims processes, the Government minimizes or refuses to recognize aboriginal rights, often insisting on the extinguishment or non-assertion of aboriginal rights and title, and favours monetary compensation over the right to, or return of, lands.” When people abandon that hopeless process and turn to the courts, Anaya continues the thought: “In litigation, the adversarial approach leads to an abundance of pre-trial motions, which requires the indigenous claimants to prove nearly every fact, including their very existence as a people.”

The judgement says: “And what about the long period of time during which land claims progress and ultimate Aboriginal title remains uncertain? During this period, Aboriginal groups have no legal right to manage the forest; their only right is to be consulted, and if appropriate, accommodated with respect to the land’s use.”

This is a far cry from the Special Rapporteur's recommendation to Canada on this subject. Paragraph 99 of his May report states: "Resource development projects, where they occur, should be fully consistent with aboriginal and treaty rights, and should in no case be prejudicial to unsettled claims. The federal and provincial governments should strive to maximize the control of indigenous peoples themselves over extractive operations within their lands and the development of benefits derived therefrom."

Another statement by the Special Rapporteur resonated throughout the judgement: “…the Government appears to view the overall interests of Canadians as adverse to aboriginal interests…” McLachlin talks only about “reconciling aboriginal rights with the interests of all Canadians;” she never describes the task of reconciling the interests of Canadians with aboriginal title and rights.

One thing is for certain. The Tsilhqot'in have exhausted the domestic remedy. Indigenous peoples have the internationally recognized right of self-determination - and Canada's overpowering regulation and infringement is a violation of that right.

Comments on the case

Chief Roger William, Xeni Gwetin, Tsilhqot'in, made a heartfelt statement in a press conference at the Union of BC Indian Chiefs offices in Vancouver, shortly after the Court's announcement. He spoke of how long the journey has been, and how many of the revered Tsilhqot'in Elders who testified during the trial are no longer here to to enjoy the ruling. He gave thanks to them but also mentioned many non-native organizations and acknowledged the importance of their support.

“The assertion of crown sovereignty and the denial of First Nation rights is still at the heart of the debate. Somehow the superiority of Canadian instiutions and governments over First Nation institutions and governments is still being based on findings such as “semi-nomadic peoples.” And this somehow means you do not have the same rights as other peoples.” – Robert Morales, November 8, 2013, in Ottawa at public conference after the Tsilhqot'in day in Supreme Court.

Russell Diabo, a policy analyst from Kahnesatake, noted about the meaning of the decision that, “I think there is a legal view of the court decision and a policy view, based on my experience on how the feds and provinces have treated the Delgamuukw and Haida decisions.”

"The court has declared that aboriginal title exists and that title is not contained to village sites and small tracts of land. "We believe that the high curt has applied common sense and the law to rech this long overdue conclusion. We do have title, it is not extinguished and it extends across our traditional territories," the Chief states." - Secwepemc Nation Tribal Council press release, Tribal Chief Shane Gottfriedson.

Grand Chief Stewart Phillip, President of the Union of BC Indian Chiefs, was quoted as follows: "It only took 150 years, but we look forward to a much brighter future. This, without question, will establish a solid platform for genuine reconciliation to take place in British Columbia." The Grand Chief also reported how intervenors hostile to the Tsilhqot'in position pleaded with the Supreme Court judges that "chaos" would befall the BC economy if a declartion of aboriginal title was made.

File attachments:

- Vous devez vous identifier ou créer un compte pour écrire des commentaires

The site for the Vancouver local of The Media Co-op has been archived and will no longer be updated. Please visit the main Media Co-op website to learn more about the organization.

Commentaires

Bruce Clark on SCC 'Expropriating Indigenous Sovereignty'

Contrary to the effusive propaganda, the only winners, as usual, will probably be lawyers.

"The constitutional law of Indigenous territorial sovereignty is ignored by the decision of the Supreme Court of Canada in the case of Tsilhqot'in Nation v British Columbia, 2014 SCC44.

The court held that section 35 of the Constitution Act, 1982, and its own recent decisions discussing that section, has vested in the non-native courts the jurisdiction to expropriate indigenous sovereignty in the public interest..."

http://dissidentvoice.org/2014/07/the-rule-of-law-vs-the-rule-of-judicia...

See also: Clark: Immunity from Prosecution For Genocide

http://dissidentvoice.org/2014/07/immunity-from-prosecution-for-genocide/

"...At all material times since 1876 the Attorney General of Canada has been the architect and implementer of the legal state of affairs under which regime the unconstitutional genocide has been implemented and as to which the judiciary and the legal profession has maintained a steadfast willful blindness. See, for example, Tsilhqot'in Nation v British Columbia, 2014 SCC44.

My indigenous former clients, the sovereigntists want their land, not the money..."

First Nations Mistaken in Their Celebration of Supreme Court Ruling - by Ian Mulgrew

http://warriorpublications.wordpress.com/2014/07/01/first-nations-mistak...

"Welcome to Colonial Courtrooms', should have been the title of the Supreme Court of Canada's landmark aboriginal rights judgment.

This decision is a death knell for their dreams of sovereignty and the opening bell for a new native land-and -resource exploitation rush..."