STORY about Environment posted on May 18, 2010 by mike

Saving Bute Inlet from General Electric

Independent (threats) Power Producers (IPP's)

Also posted by mike:

Also in Environment:

Reflections on the Bute Inlet project, travel and research.

In the second week of April, I traveled to Quadra and Cortes Islands, in the northern Gulf Islands, which are within 20 kilometers of the mouth of the Bute inlet. I talked to the people I hitchhiked with, from Courtenay to Campbell River, Quadra Island and Cortes Island about the Bute Inlet Hydroelectric Project, which consists of a series of 17 dams in a pristine wilderness area.

“Ninety-nine percent of everyone on the island are against that project,” said Brian, a volunteer firefighter on Quadra. He told me that Bute Inlet has been widely talked about on the island, both as a hydro project and for it's diverse ecology presented by local residents of the Bute Inlet.

Do locals need this project? This work?

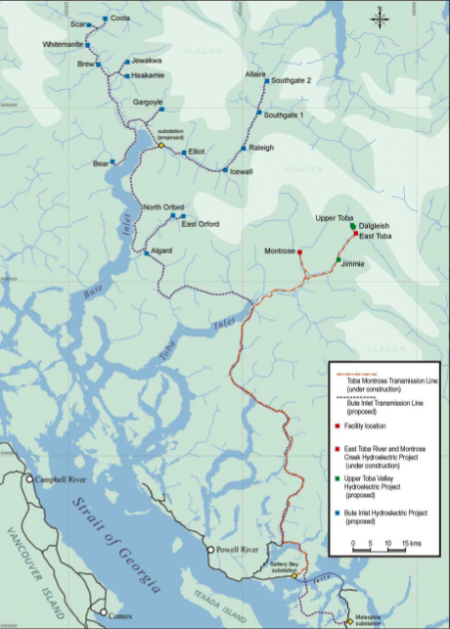

“No,” said Germain, a Cortes Island construction worker. “We haven't thought it was really going to happen anyway. No one around here is looking for it. We thought the Toba project wasn't happening; the local Indigenous people weren't into it, until suddenly they were and suddenly the project is on. It's mostly the Indigenous community working in Toba.” Toba Inlet is south of Bute. It's not totally clear what's going on and where, but what is certain is that Toba Inlet is well under way, with a camp of workers reportedly between 100 and 200. What could happen in Bute Inlet, is happening in Toba. The difference though is the scope of the project.

As I arrived on Cortez, my lift Kevin told me how his wife had worked in Toba for Kiewit and Sons.

“It's a shit show,” he told me. “A job that was three people cooking for a camp of 40 or 50 workers when she started turned into her cooking for 100 people by herself within 3 months. She said it was no problem, but she wanted more money, they said they didn't have more money,” so she quit.

We talked more about the ecosystems in the mainland south coastal region, and laughed about the way roads had washed out in a single afternoon of rain. There are logging operations in Bute Inlet, I replanted them, but there are not many roads. The logging industry uses helicopters to fly in workers and fly out logs, as access is difficult and road building not the choice they've made.

What’s in store for Bute Inlet?

The Bute Inlet Hydroelectric Project is a pressing matter of concern to local residents, community and environmental organizations.

Proposed by Plutonic Power and General Electric, respectively at 51% and 49% of Bute Power Corporation (though the name Plutonic is more common in reading or talking about the project, but nobody knows why it seems), and being developed by BC contractor Kiewit and Sons, the project has advanced discretely until residents realized that “that something was going on in the inlet” according to Laurie Wood, a member of The Friends of Bute Inlet. The project consists of 17 hydroelectric facilities on the 16 rivers feeding the Inlet, that together have a capacity of 1030 MW.

A basic assessment written by the Plutonic Power Corporation notes “a considerable number of rare ecosystems, plants, and animal species could be affected by the construction and operational maintenance of the Project” (PPC's Revised Project Description, December 19th 2008).

Public consultations where held in Powell River and Sechelt, which confused and concerned residents who live a lot closer distance to the site of the proposed projects. After contacting a local MLA in Campbell River, and expressing a strong desire to be consulted, the residents managed to have PPC schedule a public meeting in Campbell River. “We arrived and saw that the building was quite full, there was a very diverse group of people who had come. There were industry workers, environmentalists, families” Lannie Keller told me. “We were nervous because we thought that this could go either way.” But by the end of the meeting, Lannie tells me there was a strong unity, a very small number of interested individuals and a very diverse majority expressing concern and opposition to the development of Bute inlet.

The Friends of Bute Inlet formed to inform themselves and the public of the current project, the process of application and environmental assessment, as well as the ecology of Bute Inlet and the environmental impacts associated with the development of all the major drainage systems of that Inlet.

Currently, the company has postponed its Environmental Impact Assessment. Plutonic spokesperson Elisha McCallum admits the company needs more data, and says that a better understanding of fish populations is necessary. “There may be situations where we find out there may be fish coming back to areas we didn't know there were fish coming back to,” she said (Courier-Islander (Campbell River) 2010, http://www.buteinlet.net/node/165).

During a community conference titled Saving Bute Inlet from GE (General Electric), on April 6th in Vancouver, Gwen Barlee from the Western Canada Wilderness Committee expressed that now is the time for studying salmon stocks, that spring is when the water is clear, and later the water will be more cloudy.

Battling Bute in Vancouver

Laurie Wood, a member of Friends of Bute Inlet, who lives at the entrance to Bute Inlet, came to Vancouver to speak at the April 6th conference. “Bute is known as the most extreme coastal terrain, with glaciers and ice fields pushing rock slides from every cliff. From the water everything is a cliff or valley. Every valley has a river that can change places in the year. Good luck installing an industrial project.”

Over the last seven years, Independent Power Producers (IPP's) have staked over 800 BC rivers, mostly in the southern coastal region and Kootenay region of southern BC (map of current applications and granted licenses). The number of applications received and the number of applications granted have both increased directly following the government's announcements of the BC Energy Plan and Bill 30, the Utilities Commission Act, which “[removes] local government from the responsible development of clean, renewable energy sources.” (Squamish – Lillooett Regional District Press release).

Laurie showed pictures of washed out roads, whose tonnes of gravel end up in the inlet. She showed pictures of ecosystems and animals; rivers, wetlands, ice fields, glaciers, the swirling blue-aquamarine-green of glacial runoff in the deep, dark ocean waters. Laurie spoke of the grizzly bears, and birds and fish. The audience was in awe; I don't remember too many details of the words, just the images of things I didn't know were there.

I planted trees in Bute Inlet. I saw that it was beautiful. Even if I saw mostly our live-on boat, a helicopter and clear cuts, I saw that we were in a place that was enormous and extreme. “You can't help but exaggerate when talking about something that is an exaggeration in itself,” said another presenter at the conference, quoting writing from the first European travels into Bute inlet some 140 years ago.

Laurie was not one of the ecologists, or labour organizers, accustomed to presenting in front of groups. She was a local, speaking about learning how to interface with government and industry, and how to organize a resistance in a community. Her spirit seemed lighter as she spoke about the extreme country and the unlikelihood of the whole project of building being possible. She mentioned briefly the Chilcotin War, and “the first capitalist to be stopped by Bute.” (Fascinating forgotten/hidden history of the colonization of this territory, a Tsilhqot'in chief named Klatsassin having declared war to protect his peoples territory. The colonial government called it murder, an interesting difference; Klatsassin, defended himself only by saying that this was not murder, but an act of war against invaders.)

I was impressed by the conference, and the presentations to an overflowing room. Two or three of six presenters made clear statements that future development and resource projects would have to be acceptable to the First Nations. That was positive, but also means that three or four presenters did not mention this. There was frustration and motivation in the room of mostly older but some younger folks. There was a clear “ruling class” analysis on the source of the perceived problem, but I felt the reaction was more disappointed than angry. One speaker, a man with history in the leadership of the BCGEU, spoke movingly about a rearrangement of priorities; about the need for our motivation stemming from consideration of the less advantaged. I was surprised though, that even as he physically gestured towards the Downtown Eastside, he struggled to name far off places around the world.

I asked myself if community mobilization, supported by ecologists, with funding from major environmental organizations would let capitalists and colonial thinking co-opt and thwart the possibility to address the true threat to our entire natural world? Will Friends of Bute Inlet need to confront the reformist elements within their efforts? I definitely believe that the motivations of all will become clearer as discussion and planning move forward.

As I left Quadra island, I saw the biggest barge of equipment I have ever seen, being dragged by a tug boat. Storage containers, like transported by train or truck, were stacked five high, and 12 to 15 long. There were big crew cab work trucks sitting on top of the storage containers, and heavy equipment, and a crew boat. That was an industrial project being shipped; a camp, equipment and material. Who knows where it was going, maybe Bute. Definitely towards the unceded lands of the Homalco, Klahoose or the Kwakwaka'wakw Nations.

The site for the Vancouver local of The Media Co-op has been archived and will no longer be updated. Please visit the main Media Co-op website to learn more about the organization.

Comments

Kiewit

I worked for Kiewit on the Cloudworks Harrison/Stave project. Aside from the fact that 80% of its employees are from out of province, the only local hiring component they had was for menial jobs to be given to local First Nations. While there, I was informed that (a) Kiewit was "taking over" the publicly owned Upper Stave forest service road and that (b) Kiewit would receive a percentage of the profits of the profits (which the BC public will not be receiving) once it was completed.

Kiewit is among the top ten US military industrial contractors in the world and has a small army of men and equipment working in BC. You can be sure they will be awarded the Site C farmland and habitat destruction contract especially as the local Treaty 8 First Nations are now on board to the tune of $15 million a year.

It was also my observation that the more one was willing to ignore, bend or work around existing rules and regulations, the faster one moved ahead in the Kiewit organization.

Hitch hiking is dangerous

Logging in Bute is good for our enviroment because there are few logging roads? There is a frickin' airport runway out there because of logging.

Happy hitch hiking treeplanter hippies are worse at sugar coating the impact of logging than any construction company.

Thanks for the long winded article Mike.

Sincerely

Robert

PS Do locals need this project? This work? WHERE DO YOU WORK? Germain's opinion is clearly clouded probably from Cortez ganja. Not all of us can get jobs building super mansions for retired Americans over on Cortez.

if you miss understood it's probably my fault

What I meant to express, is that building roads in that area is difficult. The lumber companies have chosen another method to access their environmentally destructive resource extraction. Helicopters. No I don't think that jet fuel is green. No I am not for logging, just because I planted trees, in the past.

I work with teenagers. Do I count as a person suddenly?

Offer an opinion, please. As you are a local, I think readers would rather your take on things IN RELATION TO THE SUBJECT AT HAND.

But anti-neighbour, anti-visitor, those are interesting angles too, I guess.