Beijing Olympic Police State

Beijing Lockdown

by Geofferey York

Globe and Mail, July 26, 2008

In the small Beijing suburb of Hongxialu, there's a new force in town. The government has recruited a special unit of 288 residents, mostly middle-aged or elderly, to work as “security volunteers” in the lead-up to the Olympics.

Wearing red armbands with Olympic badges, the volunteers loiter near the entrance gates of their neighbourhood. They scrutinize every visitor and report to the police if they see anyone unfamiliar or suspicious.

The volunteers of Hongxialu are just one cog in a vast machinery of surveillance in Beijing these days. Across the city, a network of 400,000 informants and volunteers has been mobilized to keep an eye out in their communities. The old Maoist system of neighbourhood committees, which had largely fallen into irrelevance in the past decade, is being revived again as a tool of social control.

When the last gold medal has been awarded and the athletes have left, this network of informers – along with an estimated 300,000 surveillance cameras and a strengthened security apparatus – will remain as perhaps the biggest legacy of the historic Beijing Olympics.

In many ways, it is a return to China's past. “The country's labyrinthine network of law-enforcement, censorship and surveillance apparatuses has reimposed a straitjacket over the populace,” says Willy Lam, a political analyst based in Hong Kong.

This is not how it was supposed to be. In 2001, when the International Olympic Committee awarded the games to Beijing, there was optimism that the Olympics would bring political liberalization and openness to China, just as it did to South Korea in the late 1980s.

For the optimists, the 1988 Seoul Olympics were the perfect model for what could happen in China. South Korea was a military dictatorship in 1981 when it was awarded the Olympics. But by 1987, thousands of protesters were holding nightly demonstrations to demand democracy.

The protests led to a political crisis in South Korea. Olympic sponsors were worried, and there was speculation that the Olympics might be shifted to another city. To avoid the humiliation of losing the Games, the military regime agreed to rewrite the constitution and hold a free election – the first democratic presidential election in the country's history. Historians agree that the Olympics were a key factor in bringing democracy to South Korea.

But if Seoul was the dream, the reality in China is much different. Those who hoped for a democratic transformation of China should have noticed that the Olympics have often been held in authoritarian regimes without producing any political change. Seoul was the exception, not the norm.

More typical examples were the 1936 Berlin Olympics, the 1968 Mexico City Olympics and the 1980 Moscow Olympics. In each case, the Games failed to dent the authoritarian systems.

The 1936 Berlin Games were a glorification of Nazism (and the birth of the Olympic torch relay, which played such a big part in Beijing's propaganda efforts this year). The 1968 Games were held in a climate of repression, just 10 days after Mexican security forces opened fire on student demonstrators, killing hundreds.

But the best parallel to the Beijing Olympics might be the 1980 Games in Moscow – the last Olympics to be held in a Communist country.

Just as in China today, the 1980 Olympics were exploited by the host government to glorify its political system. Just as in Beijing today, the Soviet authorities used the Olympics as an excuse to round up dissidents, the homeless, and anyone else who might embarrass the government. Ordinary citizens were forced to wait years before the first stirrings of change in their country.

The 1980 Olympics failed to bring any political improvement to the Soviet Union. Will it have the same failed legacy in China?

So far, it seems clear that the Beijing Olympics have led to a deterioration of human rights and freedom in China. “It has reversed the clock,” says Nicholas Bequelin, a China researcher for Human Rights Watch. “Over all, the Games are having a negative impact on human rights. It has stunted the growth of civil society and civil organizations.

In the lead-up to the Olympics this year, China has revitalized its mechanisms of social control, including the neighbourhood committees, and allowed the Public Security Ministry to become the dominant power in the government, Mr. Bequelin said.

“Public Security has been put in the driver's seat for the preparation of the Olympics, and that's why we see so many unjustified and unreasonable restrictions. And once you give these powers to the security ministry, it's hard to take them back.”

China has made little secret of its security obsession. It has officially declared that “safety” is the top issue for the Olympics today, far ahead of any issue of athletic success or environmental cleanliness. China's state news agency, Xinhua, says the traditional goal of every Olympics – to be “the best Games in history” – has been replaced this year by a new goal: “Safe Games.”

To achieve this goal, China has called for “people's warfare” – an old Maoist term that was rarely used until this year. “We should mobilize the masses of the people to contribute to the security of the Games,” said Zhou Yongkang, a senior member of the Communist Politburo.

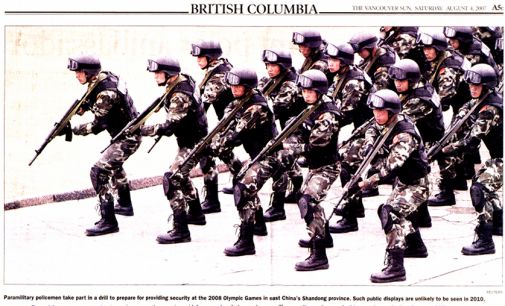

The mobilization will reach far beyond the neighbourhood committees. There will be 100,000 police and soldiers in an anti-terrorism force. There will be thousands of special volunteers in the Olympic venues – and many of these will be plainclothes security agents, China said this week.

The mobilization of this far-reaching surveillance network has been accompanied by a crackdown on dissidents, social activists, petitioners, lawyers, ethnic minorities, and anyone else considered a potential troublemaker or embarrassment to the authorities at the Games.

Dozens of activists and writers have been jailed or forced to leave Beijing. Lawyers who represent troublesome clients have lost their licences. Thousands of foreigners have been forced to leave China because they cannot get their visas renewed. Thousands of Tibetans and Uyghurs have fled Beijing because of police harassment – and because landlords and hotels won't let them stay.

Wan Yanhai, an outspoken AIDS activist, is planning to leave Beijing for the duration of the Olympics. “Many people we work with are leaving,” he said. “In the past two months, the police have followed me for a total of 10 days. It never happened to me before.”

Some of the restrictions have gone to absurd extremes. Outdoor gatherings, even concerts, have been cancelled. Street vendors and recycling men have been cleared away. Many hole-in-the-wall shops and cheap restaurants have been ordered shut, apparently because they are deemed too small or unsightly.

At many nightclubs and bars, the authorities have effectively banned live music, refusing to grant the licencesthat are necessary for concerts. Even the few foreign musicians who do manage to play in Beijing are required to seek official approval of their song lyrics. For the denizens of Beijing's famed underground rock scene, the Olympics have become the day the music died.

“This government is bent on recentralizing policy and authority generally, so this tightening will not be temporary,” said Russell Leigh Moses, a political analyst in Beijing.

“I think that we will look back upon these Games as representing not a move towards political reform or rethinking power but bolstering the confidence of officials that they can indeed micromanage events.”

Some of the new restrictions – including the tighter controls on visitors and foreigners – will not only remain in Beijing but will probably be extended to other cities, Mr. Moses said.

“For all too many officials, these Games are not about international co-operation but about Chinese power,” he said.

If the political legacy of the Beijing Olympics is likely to be limited or even negative, the economic and environmental legacy will be equally minimal.

The new Olympic architecture has gained global attention, but its economic impact is negligible. National spending on Olympic infrastructure has boosted Beijing's economy by barely 1 per cent, analysts say.

Short-term spending by Olympic visitors will be counterbalanced by the losses at factories that are being shut for environmental reasons. And since Beijing provides only 3 per cent of China's national output – far less than the economic share of most Olympic host cities – the Olympics will do almost nothing for the Chinese economy.

The environmental legacy of the Beijing Games, finally, will be marginal. New subway lines will be helpful, but the smog is likely to return as soon as the Games are over. Beijing has managed to reduce pollution slightly in the past five years, but the number of “blue-sky days” has increased by barely 10 per cent in that period.

Even with rules to slash the number of cars on the streets of Beijing this week, the improvement in smog levels has been modest. Pollution levels returned to dangerous levels on Thursday – five days after the new traffic system had begun.

When the Olympics are over, Beijing's streets will be jammed with traffic again. For the millions who watch the Olympics on television or in the stadiums, the Beijing Games will be a pleasant memory – but life will return to normal, with none of the reforms that the IOC had fantasized about.